Default Delete:

Photographic Archives in a Digital Age

August 1, 2017

Kris Belden-Adams edited a nice (and irresistably titled) new volume, Photography and Failure: One Medium’s Entanglement with Flops, Underdogs, and Disappointments, published by Bloomsbury.

Here’s the publisher’s description:

Throughout photography’s history, failure has played an essential, recurring part in the development and perceived value of this medium. Exploring a range of failures – individual and institutional, technological and historiographical – Photography and Failure asks what it means to fail and considers how this narrative of failure has shaped our understanding of photography.

I am happy to have a chapter in the book, “Default Delete: Photographic Archives in a Digital Age”. Here’s how the essay starts:

Several years ago, my computer’s hard drive crashed and I lost a couple of years’ worth of my own digital photos. They were pictures of my toddler-aged son, mostly, and our young family (he was the first child, and correspondingly well-documented). For someone who had recently finished a doctoral dissertation revolving around photography archives and family albums, and who backed up text files with a fervor that bordered on obsessive, I’d done a remarkably poor job of establishing any safeguards for what I would have told anyone were among my most cherished photographs. When it became clear that the images were irretrievable I felt crushed, and hated the part of myself that routinely fails to adequately address matters of logistical life maintenance. Something had failed, but what? Was it me, was it “photography,” was it “the archive”?

Over time it became more apparent that because of all the photographs from those years that I’d shared—through social media posts, attached in emails to friends and family members, included in gifts of little books and custom photo calendars—I still had more photographs documenting that couple of years of my son’s childhood than I did from the corresponding years of my own childhood. Many of the “lost” photographs, it turned out, were remarkably persistent; the failed archive had already been dispersed into new contexts.

Through cultural customs, theoretical musings, institutional expectations, and the rhetoric of technological progress, photography—in nearly all of its iterations—has come to be very closely associated with an expectation of permanence. And yet, the image eco-system today—fueled by the rapid rise of social media, and mobile technology in particular—has transformed the role of the digital photographic image as it is circulated, shared, saved, discarded, and recontextualized with speed and ease. These changes reflect the adaptable realities of formats like jpegs and gifs in lieu of traditional gelatin silver or cibachrome prints; viewing platforms such as mobile phones and tablets instead of magazines or galleries; and the near-instantaneous sharing enabled by Twitter and Instagram instead of print circulation or photo albums. These shifts deeply challenge a field built (largely in the last 40 years) on finely crafted prints, display in traditional gallery and museum spaces, and the printed photographic book tradition, and, as such, call for new tools of analysis and methods of evaluation.

What I experienced was not a failure of photographs, or of photography. Rather, if anything, it was a widespread failure to either allow or account for a role of ephemerality in the medium. In a way, my experience with photographic loss indicated a success of photographic endurance, no matter how accidentally achieved. Counter-intuitively, a greater recognition of the nuanced ways in which photographs may—or may not—disappear, whether from material or digital realms, may mark the emergence of a culture that, despite itself, can come to value photographic impermanence in the face of an all-consuming default archive.

Printed family photographs circulated as discrete material objects that were traded and collected as cartes-de-viste, gathered into albums, and tucked into wallets. The object-ness of those photographs was both a matter of fact, and a mechanism for social engagement, whether at the time of the photograph’s staging and production, or after the fact. In comparison, digital photographic images that circulate on social media can be widely and quickly distributed, are easily searchable, and often thematically aggregated through tagging. Yet at the same time, they also may disappear as quickly as they emerge, or become lost in the digital flow of imagery. Beyond losing a hard drive, or using one of the increasingly prevalent options for temporary social media sharing, images seen online or among a stream of posts can be nearly impossible to find a second time. Indeed, a central question of our current photographic eco-system revolves around developing a more nuanced understanding of the ways in which photographs appear and disappear. This is a question that affects both printed images (photographs-as-objects) and “immaterial” images (photographs on screens), though it may be the latter category that more robustly accounts for lived daily photographic engagement. Each broad category of image is subject both to staggering accumulation and rapid disappearance and, in fact, those very accumulations are often deeply connected to disappearance, as sheer quantity produces an inverse relationship with accessibility.

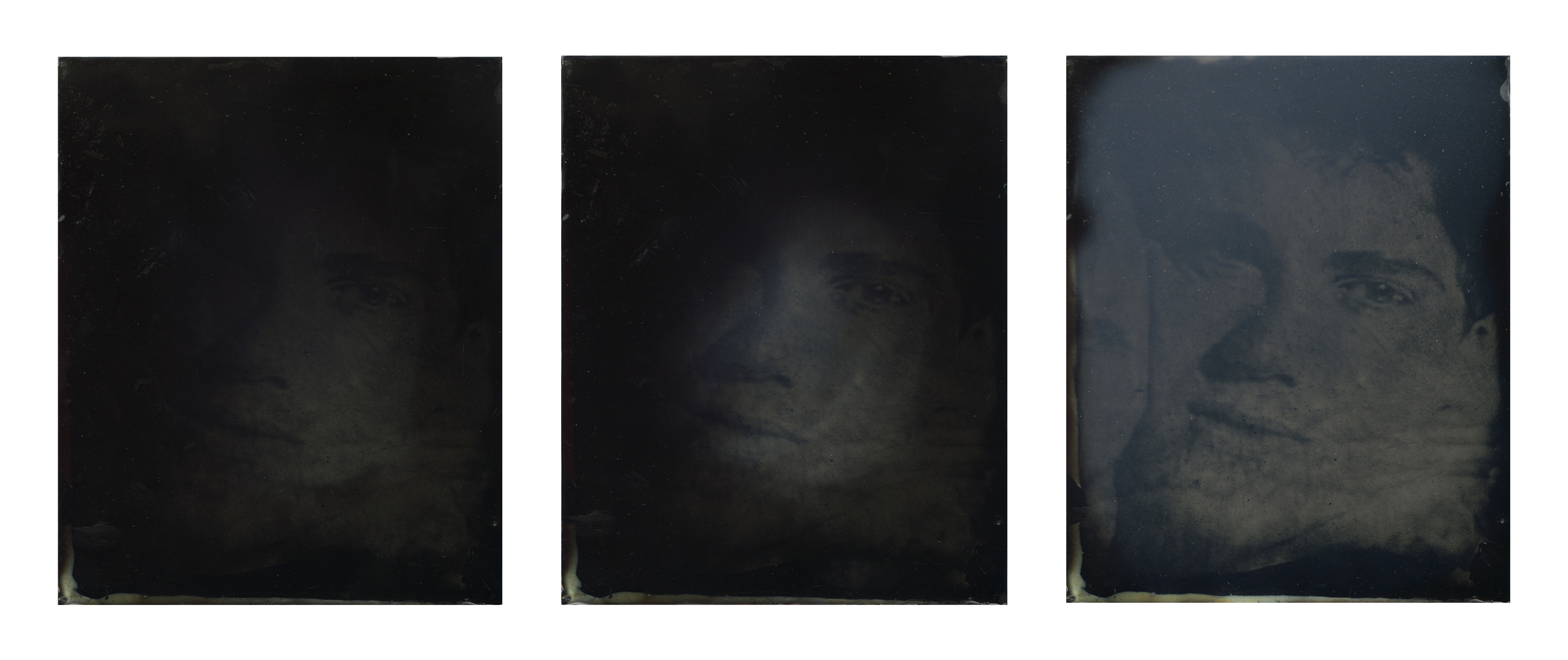

I wrote a bit about the work of artist Brian Ganter:

The recent work of artist Brian Ganter is concerned with film stills, sourced online, of gay pornographic movie actors who have died from complications of AIDS. However, those stills become largely un-viewable. Ganter covers the surface of the photograph—whether made on paper, metal, or glass—with a matte black heat-sensitive coating that obscures the image. The faces of Ganter’s subjects exist perpetually underneath this black thermochromic pigment, and must be revealed through the application of heat. Thus, viewers must break typical art-viewing protocol not only by touching the prints, but often, by breathing onto them or holding the objects directly against their warm bodies to fleetingly reveal the image. In this case, the shared experience of the ephemeral image is fully visceral and intimately experienced, available only for a small number of viewers in close proximity to the work. The process of viewing entails an unusual level of commitment and physical involvement, thus necessitating a highly invested viewer. To speak nothing of the visual content, watching the underlying images emerge and then, slowly disappear again, engages viewers in the moving process of creating tenuous, ephemeral photographic images.

And Phil Chang:

In 2012, the Los Angeles-based artist Phil Chang presented a series of photographs titled Cache, Active. The title itself suggests a secret and dynamic stash, which in fact aligned with the contents of the exhibition: twenty-one matted and framed 11-by-14-inch unfixed photographic prints that began to change immediately upon being exposed to light at the exhibition’s opening. Chang’s subjects were an array of photographic conventions: portraits, still life, landscape, and abstractions – so as not to slip into a reading based primarily on the subject matter of the image. One reviewer described the show this way in Artforum: “Presenting photography as a durational performance, the artist literally unveiled the works at the opening, exposing them to the gallery’s bright fluorescence, which gradually darkened the pictures until, after several hours, all appeared a uniform dull maroon tone.” For the remainder of the exhibition, the photographs appeared as monochromes.

Chang suggests a shift in our understanding of where the importance of photographs lies: in our minds, with the object, or in the image. By extension, the viewer may also wonder which, if any, of the billions of photographs made on a daily basis in our culture do we want or need to last. More fundamentally, though, the series challenges the notion that a photograph’s value is equivalent to that of the image it presents. Importantly, Chang’s images have two primary modes of existence: first, in the period of their visibility, and second in their “monochrome period.” Of the former, the scholar Walter Benn Michaels notes: “There is an important sense in which you don’t simply look at these photographs, you watch what they’re doing; it’s a kind of performance.” And, like a live performance, it is ephemeral.

If you’d like to read the rest, here’s a pdf.