Words & Pictures:

Or, This Year's Baobab Trees (On Martine Syms, Kerry James Marshall, and enigmatic conversation)

October 9, 2017

I am posting this essay in May, 2024… a full six and a half years after I wrote it. It was an important essay for me to write, as it was among the earliest in which I leaned into the kind of elliptical connections that have since come to characterize some of my favorite essays. I didn’t share it, though, I suppose because I thought it wasn’t scholarly enough, or that it was too personal, or that both of those things were true. This has come to be a familiar back-and-forth in the internal monologue of my brain, but, on the other hand, it is in fact often the way I think and write. So, without apology or caveat, “Words & Pictures, Or, This Year’s Baobab Trees” (2017).

1.

There’s something I find pretty appealing about reading strangers’ text message threads over their shoulders. I don’t feel this way at all about passively overhearing strangers’ phone conversations (I’d rather they keep those to themselves), nor do I have any interest in reading text threads on my friends’ phones (that’s just an uncomfortable invasion of privacy). But quiet access to something otherwise hidden presents just enough of a window in another person’s fully separate life to allow either an element of surprise or an imaginative opportunity. Recently, while boarding a flight, by way of this kind of visual eavesdropping, I learned the woman inching her way down to her seat in the aisle ahead of me was part of an effort at her church that involved therapeutic hugging. What a nice thing to know about a stranger.

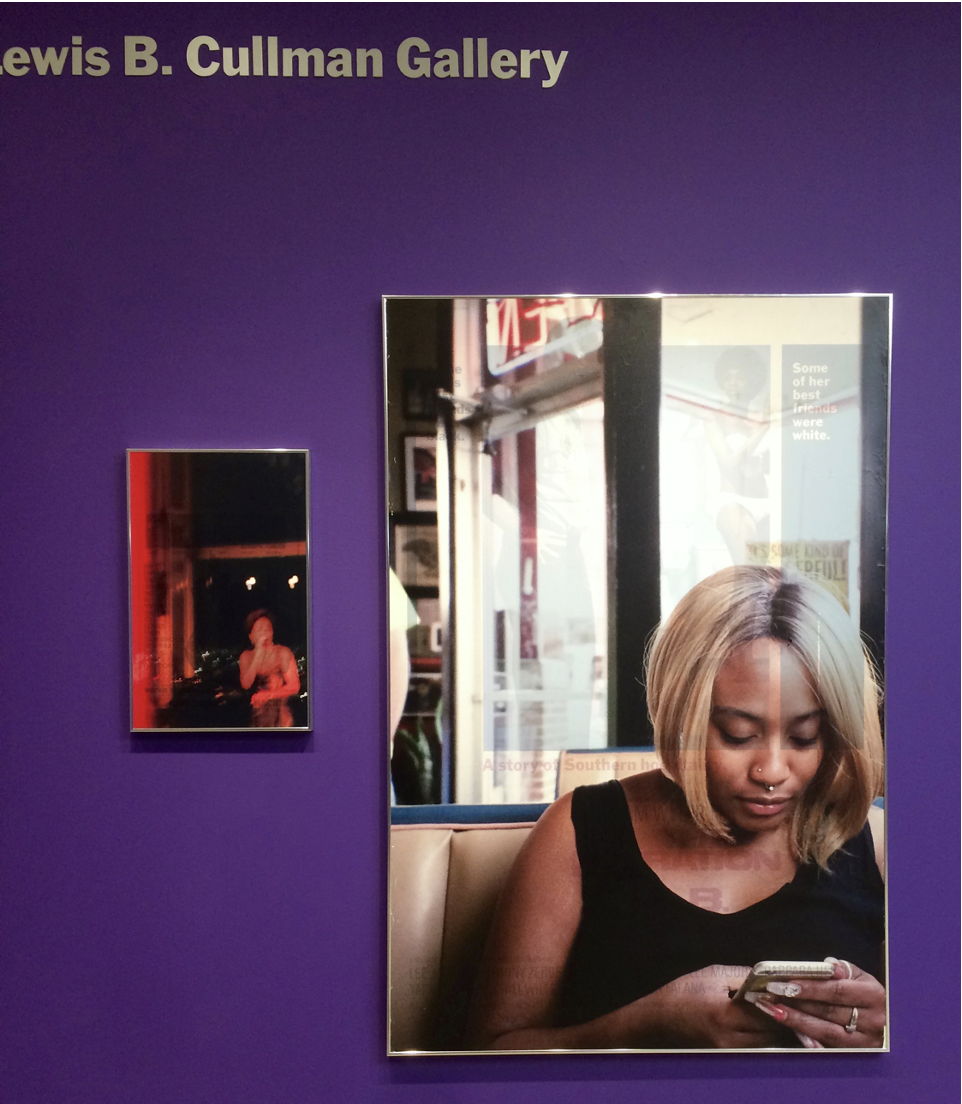

I thought about this window that I had had—or imagined I had had—into the world and psyche of the hugging woman while viewing Martine Syms’s recent exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Among Syms’s innovations is her recognition of the layering at hand in our use of and exposure to contemporary photographic communication and media. She’s also keenly interested in bringing a vernacular voice—the way we talk and communicate now—into the realm of her work. In addition to the photographs and videos on view, visible to all, the show offered an element of integrated augmented reality, exhibition content that would be accessible to us only by way of downloading an app to one’s phone. Since my friend didn’t want to download the custom app, I did: its acronym is WYD RN, which I only later figured out means: what you doing right now.

One of Syms’s photographs showed a woman, seated in a beige booth at what appeared to be a diner, slightly hunched, in that now familiar 21st century posture, over her phone, which she held closely with both hands, cradled within her extravagantly long and brightly polished fingernails. Her gaze was downwards, her experience fully within the world of her phone. This is the visual subject of countless photographers seeking to critique their subjects’ digital/online absorption, typically imagined as the subject’s loss: a loss of engagement with the lived world, a lack of attunement to the simple observed pleasures of light reflecting and refracting in the windows behind the woman, a disconnection from the very person (us, the viewer) occupying the seat directly across the diner’s table. But Syms, I’m guessing, is uninterested in this type of critique—and to keep us from making the same mistake, she shares some insider knowledge, letting us peer one step beyond the outer surface.

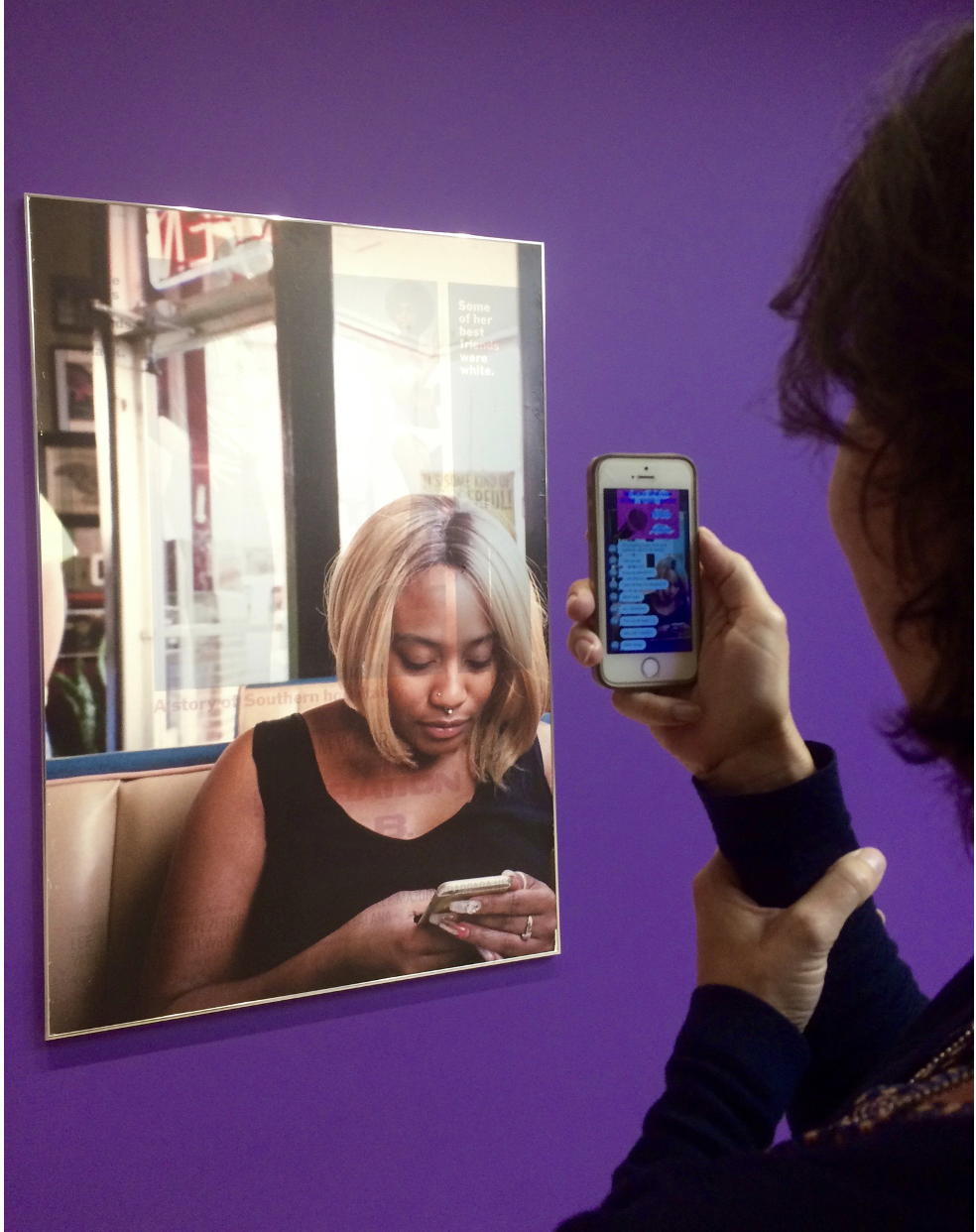

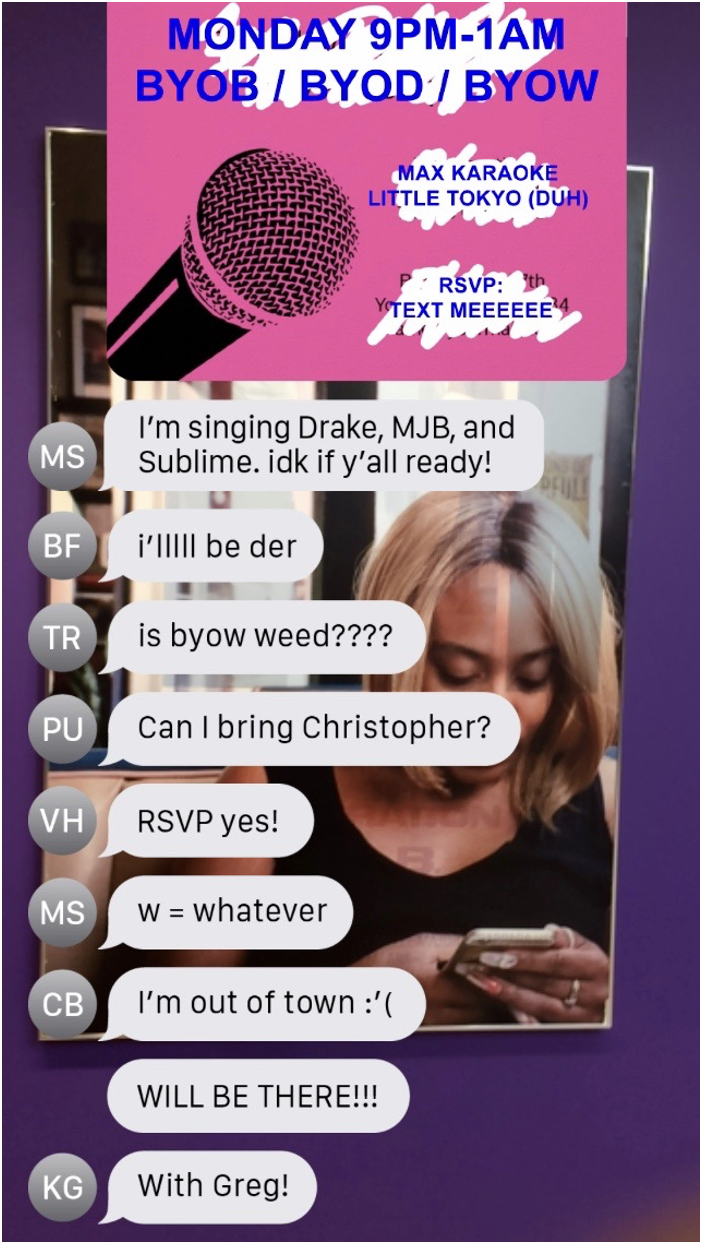

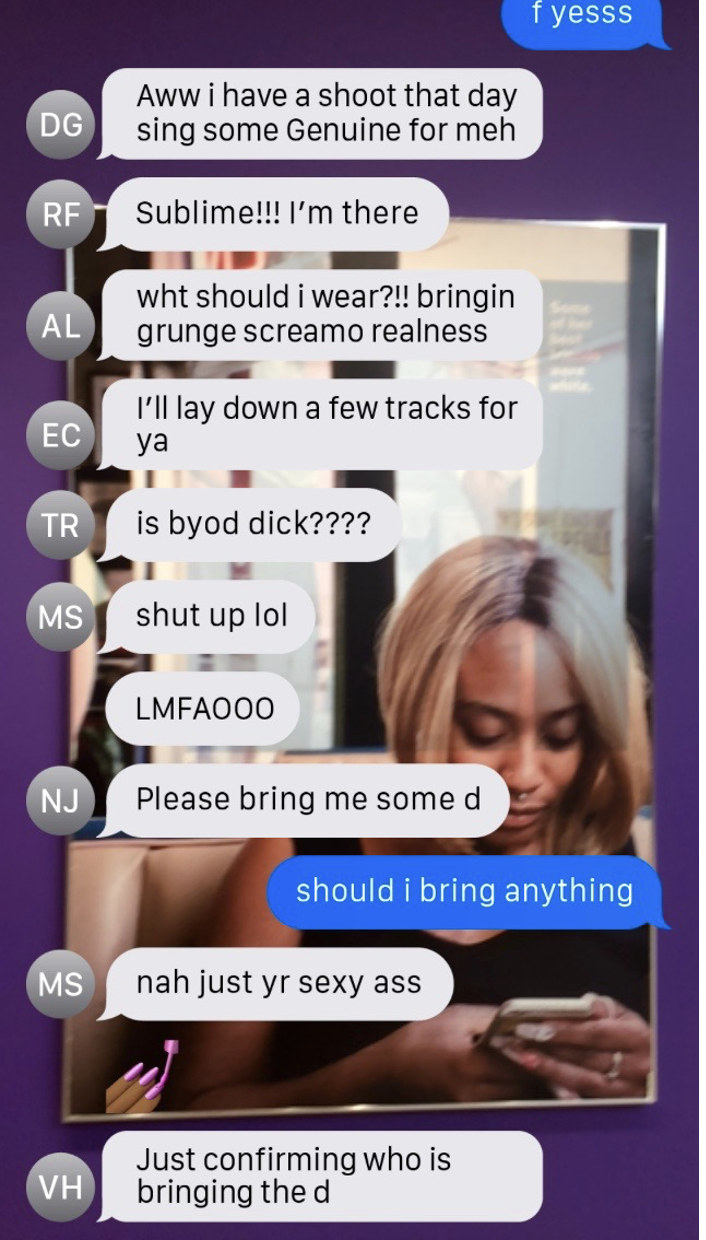

A viewer, holding her own phone’s camera up to Syms’s photograph, with Syms’s WYD RN app installed and running, sees on her own screen a “live” feed of rapid-fire group texting, becoming privy to the social life and conversation of the woman in the photograph. My camera, along with the app, “reads” Syms’s photograph, recognizes it, and ups the intimacy ante, producing what feels a whole lot like an over-the-shoulder reading of the rapidly unfurling text thread of a stranger.

But instead of a hugging church-goer, Syms shares the evening’s karaoke party plans of her subject, exchanged in a set of voices that couldn’t be further from the typical “voice” of either education-department-approved museum labels or International Art English.

Syms’s provocation is also slyly gestural: in order to fully view the artwork on display, viewers must enact a physical movement—holding a camera up to the artwork, as if to photograph it—that is exactly the same as that of the 21st century museum-goer’s gesture of snapping her own souvenir snapshot of the artwork on view. As the argument sometimes goes, this kind of “engagement” isn’t really engagement at all, but rather a new form of distraction and deferral. But in Syms’s work, it’s figured instead as a mode of access: access to a temporally and geographically-specific experience; access to the private communication on a stranger’s phone; access to a different perspective altogether. And then, once you, the viewer, put away your own phone, the conversation disappears.

2.

To be intimate implies that a mutual understanding between people, an agreement of sorts that barriers might be negotiable, semi-permeable. One person gives permissions, utters the secret password allowing the other at least an attempt to pass beyond the skin. I am spending my days in her archive, opening boxes and manila folders, my hands muffled in white cotton gloves. Maya Deren has not consented to my investigations, my insinuating closeness….A photograph is a transaction between different modes of time. I want to open negotiations with that sealed moment. Mark Alice Durant

Reading the essay from which the above is excerpted, in Mark Alice Durant’s highly readable, smart, funny and heartfelt recent collection of essays, 27 Contexts, I recognized the experience of my past year of research immediately. That recognition was accompanied by an immediate sense of discomfort at this moment of strong identification. Durant, an artist and writer, is reflecting on his own identification with his research subject, the experimental filmmaker Maya Deren. I can recognize that outside of its context—maybe even inside its context—Durant’s reflections contain, for me, a kind of queasy discomfort, surfacing a potential critique of the intrusion of a male/future gaze into the apparently glorified and subtly sexualized hidden wonders of a female/past subject. And yet, I knew exactly what he meant. I had been riveted, had my own archival fascination, with another intellectual woman whose work, like Maya Deren’s, finds it heart and origins in 1940s New York, with my own powerful sense of intimacy with someone long deceased and what must be (mustn’t they be?) my own projections of her life and work.

This was the photography writer and curator Nancy Newhall, who was professionally most active in New York in the 1940s, and Rochester in the 1950s and 1960s. I had long harbored a distanced fascination with her career, about which I had known little, but a series of somewhat chance-related events led me to look into her correspondence with the American photographer Edward Weston. Reading her private letters, it’s not much of an exaggeration to say, I fell head over heels. Her published voice was, to me, okay – but her voice in correspondence was irresistible. I set aside other projects, even professional obligations, so I could spend more time with this voice. It was not unlike how one might rearrange responsibilities, and put some off entirely, to spend time with a new love. Though I’d loved my research projects before, this particular version of intense affection hadn’t happened to me before.

As I sat with her hundreds of letters to close friends and loved ones, and eavesdropped on Newhall’s inner thoughts, week after week, in yet another institutionally-sanctioned and approved setting (this time the archive, not the museum), I could relate both to the sensual thrill Durant described and also to the underlying reality that I was, as my PhD advisor put it bluntly over a decade ago, a nosy art historian—as the job required. I am still just as fascinated with the emotional and psychological dynamic this relationship engenders. This was the discomfort of the identification—knowing, all along, as Durant did of his view of Deren, that my attraction to Newhall was a one-way relationship, one-way affection and fascination. This, by nature, is what all historians who find themselves riveted by archival subjects, inevitably encounter.

3.

September 12, 2016

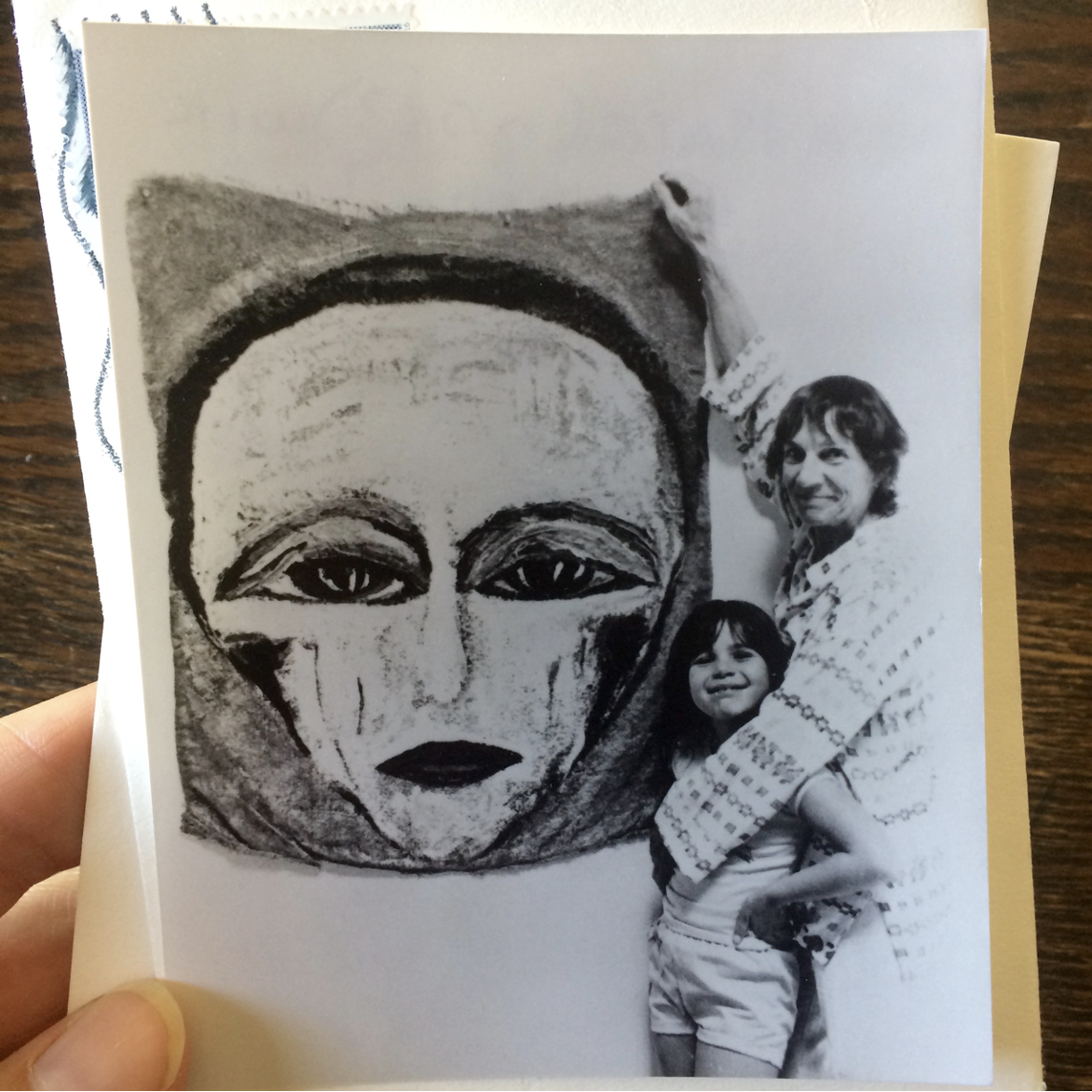

Kate, a few days ago I opened the back of a framed 8 x 10 photo Virginia had given me (a picture of herself in her studio).

…

When I took the back off the frame, I found a smaller photograph which I’d never seen, tucked into the backing.

The photo is of you -as a little girl, I can’t tell how old, maybe eight, with Virginia in her studio. I will save it for you.

Thinking of you today.

Love, Suzanne

This was a condolence note, received via email. My grandmother, Virginia, had died that day. I couldn’t recall the photo as it was described in the note, though I did, later, recognize it, as one that I’d seen many years before.

This explanation, such as it was, arrived the next day:

September 13, 2016

Kate, Virginia never told me that photo of you with her was tucked in the back of that frame, but she did have a sort of “magical thinking” mindset at times. (That is, when she wasn’t being relentlessly pragmatic)…

The note went on to describe how my grandmother had “given” me to the friend, seemingly as a means of sharing but without full explanation.

It felt strange to think of myself having been a gift, from my grandmother, to a dear friend of hers, a story that emerged to me only through the discovery of a photograph, framed and hidden behind another photograph. As if my own one-way affection was circling back on me. How to understand this? What of me was being shared? How? With whom? What could this picture tell me?

4.

This is, in a way, the question at the heart of nearly all my professional activity: what could this picture tell me? And in what kind of language? And how can these languages, on one end of the spectrum, speak across cultures and across time in the formal space of institutions—of “the museum”, of “art history”—and, yet, on the other end of the spectrum, convey the intimacy of private conversation? How does Martine Syms’s group chat, unfolding within a language developed among friends, translate to the museum? What—in the way of access, shared language, or the disruption of those modes of connection—does that dynamic have to do with the pictorial relationship of a researcher to a long-deceased subject, or to her own grandmother, hiding pictures in frames to be discovered after her own death? What—to use Mark Alice Durant’s language—is sealed information, and what is permeable? When do pictures do the work, and when does language?

The collective Kerry James Marshall fan club hit a fever pitch of enthusiasm this past spring, as his retrospective, Mastery, traveled from one major museum to the next. The thing I’d been thinking about around Marshall, in the months leading up to this visit, is how he speaks a language so close to that of art historians—that, at heart, he’s fascinated with the images we see and the ways that we come to see and understand them—so often through reproduction, the clippings of images—from art magazines, from wherever—that allow us to build our own personal archives, create our narrative histories. Marshall’s paintings had made a big impact on me in the mid-1990s, when I saw them in Chicago as a newly-declared art history major in college. Seeing them again, twenty years later—the Garden Series paintings in particular—meant remembering an early and visceral experience of what it might mean to be an art historian. I remembered looking at the paintings, for a long time, and having felt so clearly the waves of looking, as more and more happened, and unfurled, in front of me, of meaning there, in layers in the painting: the beauty of the gardens in spring, the grim reality of the urban housing projects, the painful systems of racism and economic neglect that had led to that reality, the strange overlay of the text as it floated into my perception of the image, and the utter newness of the insistently heroically-sized yet un-heroically-lived Black figure in the museum setting, imagery underscored by the presentation of raw canvas and grommets yet countered all the while by the very lushness and sensuousness of the paint and color itself.

Confronting the bitterly renewed relevance of these paintings in the culture of the 21st century United States aside, it was another artwork in the exhibition, an installation that I hadn’t seen before, that struck me most of all: the Baobab Ensemble (2003).

Here, Marshall laid out a room full of those very art magazine clippings I’d been dwelling on, the raw (reproduced) material of what comes to take form—and, often, over time, re-form or un-form—as a cumulative story of art. The images were wide-reaching in scope: a lot of art, from all historical periods, but other visual images as well.

When I got home, still in the slightly intoxicated state that viewing the show produced—I took these notes about it:

Finally, the Baobab Ensemble installation. It so figures I would gravitate to this, so totally predictable. The art historian’s version of Eric Kessels’ flickr piece, 24 hours in photos. Actually, a lifetime – so far – in images. Photographs aren’t enough. The images we see, the images we save, the images that aren’t there at all. The all-over-ness of them, the surrounding-ness of them, the inadequacy of them. The sorting and the categorizing, the book open to Marshall’s entry under BLACK ARTISTS. Art history—the practices of art history, the field’s conventions and its customs—made so vividly absurd. And yet, still, the hold of all those images in all those magazines, the effect and the wonder and the impact and the fascination… and the possibility, the promise, of losing yourself in all of it, of living in it. Dip in here or there, start the story.

5.

All of these things—micro-events, fleeting observations—happened over the last year, from September 2016—October 2017. None of them especially notable on their own: museum visits with friends, pictures that show up in email correspondence, a new book I was reading, making some notes on an artwork I’d liked. Like most photo historians, I have a fascination with the relationship between pictures and words. We’re trained to be compelled in this area, from the theory we read, to the images we (nosily) study. Mostly I think about this relationship in terms of printed words: labels, titles, stories and essays published with specific photographs, captions (even hand-written ones), now even hashtags. But as photographs, and our relationship to them, become more conversational, there’s something to be said for re-imagining the effect of words on images (and vice versa) into this realm of spoken conversation, of personal voice and fleeting exchange. Marshall’s Boabab Tree metaphor invokes a casual social encounter, a site—wherever it may be—that suggests a conversational exchange of ideas: sit here, he offers the viewer, and here’s a stool so you can stay a while. Have a look, and talk to someone.

To close, another email, another kind of voice—this one recounting a two-hour long conversation I’d had with a tow-truck driver after my car broke down 100 miles west of the nearest auto repair shop, at dusk. I hadn’t seen the Marshall show yet (it would open later that spring), but I’d had Alfred Stieglitz’s Equivalents on my mind for the class I was about to start teaching that semester. The Equivalents seek to communicate without words at all, photographs of clouds meant to convey the abstract feelings of music.

I took your advice, and brought up clouds with the tow truck driver. The night clouds were gorgeous with the big moon out in the desert, but he wasn’t too interested. So we talked for a long time about diesel engines. He hadn’t heard about the VW emissions scandal, but he knew a lot about diesel engines. Then I tried again, and told him about Stieglitz and his idea. He considered it, and kind of was interested in the idea of an image representing or suggesting a non-visual thing, and was maybe more interested that such a thing as photo history existed, and then it turned out his son had been the high school photographer, and had really loved it (now the son is a correctional officer at the prison outside of Blythe). Then we talked for a long time about ATVs and monster trucks and hydrolic lifts – turns out he has a 1979 Ford truck (those cool old ones, he showed me a picture on his phone) with lifts, he takes it off-roading in some desert dunes with the other vintage monster truck guys. Then he mentioned he spends all day Sundays, 5am-5pm, at church. I queried about this schedule, and it turns out he’s a minister. I asked him how he got into that, and he told me the story of his spiritual awakening and religious conversion, on April 4th, 2000. We spent the rest of the drive talking about this. I’d like to think that the cloud conversation put him in a confessional mood… or maybe he’s just a guy who became a minister because he really likes to talk about it. After we dropped my car off at the repair place, he left me and my 5 bags outside an empty Burger King in Goodyear, AZ, so I could call an Uber.

My conversation with the Uber driver was really boring. But I’ve thought often about the strange intimacy of the conversation in the tow-truck, its effect on my view of Stieglitz’s Equivalents since, and what window I did—or didn’t—get into this stranger’s life, maybe not so different from the windows I got in any of these stories.

[photo of tow truck minister, driving me across the desert at night]