The Value of Ephemeral Photographs, or, Everything I Know About Alec Soth I Learned on Snapchat

October 22, 2015

There is no shortage of short biographies of Alec Soth. Most of them follow standard art world protocol for any artist biography: brief personal background; significant bodies of work; notable exhibitions and publications; awards, fellowships, and accolades; and institutions that have collected the artist’s work. Some seek to provide an overarching thematic arch, others aim to humanize with a short anecdote. They’re necessarily brief, and meant to provide an overview of a career to ground the reader, listener, or viewer to whatever fraction of that career is presented to them at that moment.

In my roles over the last twenty years as gallery assistant, label-writer, researcher and lecture series organizer, I’ve written plenty of these short bios for others. And, a few months ago, I was asked to write one about Soth, to contribute to a forthcoming edition of a scholarly art encyclopedia. But as I thought about the dozens and dozens of short biographies that already exist about Soth, the assignment came to feel both more daunting and more redundant: couldn’t there be an art history bot that could aggregate the best of all the existing biographies to produce what I had been asked to do?

Soth has become an unusually public and prolific artist, and is also sufficiently beloved by a wide enough audience that anyone with at least a passing interest in contemporary American photography has had opportunity to become familiar with the basic contours of his career. The predominant storyline begins in 2004 with the twin origin stories of his inclusion in that year’s Whitney Biennial and the acclaimed publication, by Steidl, of his first major book, Sleeping By the Mississippi, and follows his subsequent major projects (including Niagara, 2006; Broken Manual, 2010; the Dispatches, and now Songbook, 2015); notes the influential role of his bookmaking and independent publishing venture, Little Brown Mushroom, in the contemporary photo book boom; and his membership in the esteemed photojournalism collective Magnum. Also, he lives in Minnesota.

I (or anyone) can know all of this without paying any particularly close attention to his career. It’s a biography of major and documentable accomplishments and a shorthand for calculating artworld value. But rather apart from these projects of obvious credibility, I had been following Soth on the ephemeral image app Snapchat for a few months, after he posted a series of musings on Twitter about the app along with his username, littlebrownmush. We’d had a phone conversation as I prepared a conference paper on ephemeral photography, but had never met: he was essentially a stranger to me. I began to wonder what a biography, culled only from his Snapchat posts, would look like. Emerging from an accumulation of fleeting images, it would be an alternative form to the conventional artist biography, certainly, but might it have a value of its own?

Biography as a fraught enterprise

The practice of writing artist’s biographies is a common one for art historians, to be sure. It was, in a sense, the foundation of Art History as a discrete field of study: Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists (published in Florence in 1550) established a set of expectations for how to look at an artist’s life and distill it in such a way that the life and the art were inextricably intertwined. But, of course, there is a certain hubris and absurdity to the idea of summarizing a life—any life—in a biography, particularly a 300-word one. (As a counter to this, think of the six-volume, 3,600 page autobiography of Karl Ove Knausgard which itself no doubt still omits the vast majority of the author’s lived experience, or the community of enthusiasts for extreme lifelogging, a clear recipe for failure.)

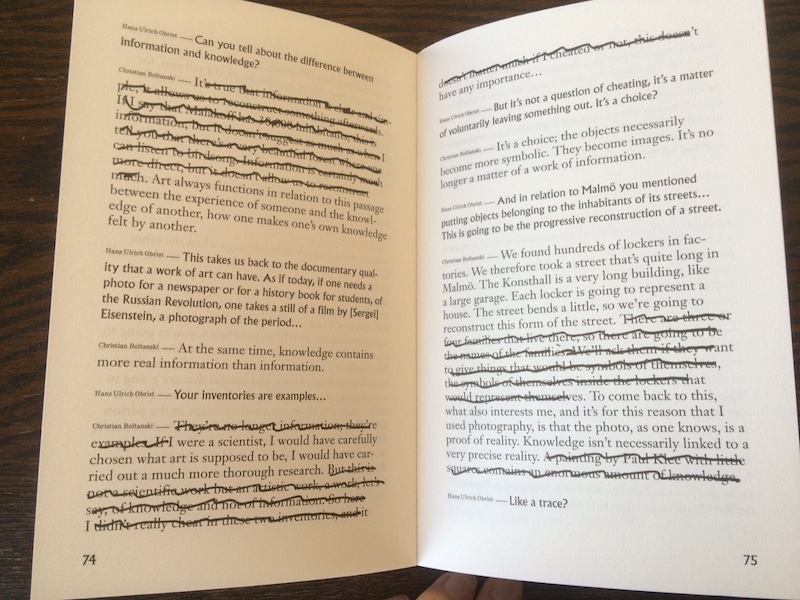

I’ve long been a fan of the French artist Christian Boltanski’s early works in which he proposes various challenges to the conventional artist/art historian relationship. This traditional relationship might be defined as one in which the art historian, at some point after the artist’s death, carefully reconstructs the artist’s life from remaining archival material. Boltanski has enacted these challenges in a range of activities and objects, from proactively dispersing his own archival materials to unusual locations, such as to a museum in Munich dedicated to, as Boltanski puts it, “a German clown”; to conducting a year-long serial interview with the curator Catherine Grenier in the form of Freudian psychoanalysis, the results of which were published in a 200-page “confession”; or his heavily redacted interviews with Hans Ulrich Obrist. But my favorite is his 1989 installation, Les Archives de C.B., 1965-1988, which is comprised of 646 closed metal boxes, stacked high against a wall, ostensibly containing the artist’s archives (or are they the archives of his alter ego, C.B.?) Seeing these high stacks of boxes on display in a museum, what is the inquisitive art historian, well trained in non-disruptive museum protocol, to do?

Boltanski, when I had the opportunity to ask him about Les Archives de C.B., said that his dream for the piece is that an art historian write his biography based solely on the contents of the boxes—as if Boltanski had died—and not consult any other material or contact him personally. (He had tried a similar experiment in 1988 with the curator Didier Semin, who was writing a monograph on the artist.) At the time I posed the question to Boltanski, I was in graduate school and considered doing it myself; ultimately I didn’t, but the proposal planted a seed for how I would subsequently think about the process of an art historian’s biographical reconstruction of an artist. Not just what, but who would I have found in Boltanski’s boxes? What traces would be left behind and have the honor (or bear the burden) of speaking for a life?

Social Media Identity

Unfolding separately from this somewhat academic interest in what it means to participate in the biographical reconstruction or representation of an artist, is the altogether pedestrian and largely unconscious activity of parsing the various identities under rapid and fluid construction by friends, relatives, and strangers on multiple social media platforms. In a manner not unrelated to the many historical ways people have used photograph and caption combinations—in cartes-de-visite, family albums, and holiday cards—to produce and circulate particular social identities, social media enables this practice—as it ranges from a hobby to a professional level—on a greater scale of magnitude and in a far more public way. There is an equal magnitude of sociological interest in just how these identities are constructed and a corresponding degree of doubt that there is, actually, much correlation at all between the real self and the social media construction. While not belaboring the point that the notion of a “real self” for a “social media self” to subsequently correspond to has been outdated in many circles for decades, it’s worth pointing out that, on the other hand, it would be the atypical social media profile that really reveals nothing about the person creating it.

Because of the way Snapchat works, it’s hard to find people unless you know them personally or come across their username in some public context. There are no listings of who other people are connected with and, because images disappear quickly, there is no archive of previously posted images by which to check someone out. Of people I’m connected with on the app, I have no idea, in most cases, of who else sees their posts. These conditions call for an extra leap of faith in connecting with someone and a subsequent sense of privacy even in viewing images that have been posted to all of someone’s followers (as opposed to the direct message version of the app which sends a photograph or video to a single person). Without knowing who else is looking, or whether they “liked” something, often images feel as if they’ve been delivered to you, personally. To me, it’s one of the most successful illusions of the app, and one I fall for again and again.

Imagine a Snapchat Biography

Of my Snapchat contacts, Soth was a bit of an outlier: while the others were friends, former students, or celebrities (I can tell you that Rihanna has a remarkably boring Snapchat feed), Soth seemed like someone I could know, but just didn’t.

So I gave myself an assignment to imagine—and write—a Snapchat biography. Channeling Boltanski’s directives, the assignment had rules: I could only write about what I had gleaned, whether through a specific image or my own interpretation of multiple images, from Soth’s Snapchat posts alone; I would need to suspend any knowledge of his career otherwise. Furthermore, the biography would have to be constructed from memory as posts on Snapchat disappear after 24 hours. From October 2014 through May 2015, this is what I learned:

littlebrownmush lives near the airport. He is a sports fanatic, favors brightly colored sneakers, and enjoys spending time with his son, who doesn’t mind being photographed. He wakes early to meditate, and works in an environment with several people who drink coffee. When photographing at night, he prefers subjects such as sirens and emergency personnel.

On his frequent travels, he partakes in coping rituals that include listening to Christian radio (in the car) and making emoji-enhanced selfies (on planes). At diner breakfasts, littlebrownmush elaborately and competitively stacks jelly containers. Train travel is a bit of a reprieve, allowing time to write, make friends, listen to live music, and bunk with Billy Bragg. Travel by helicopter or speedboat is more unusual. Though he finds it daunting, he speaks regularly to large crowds.

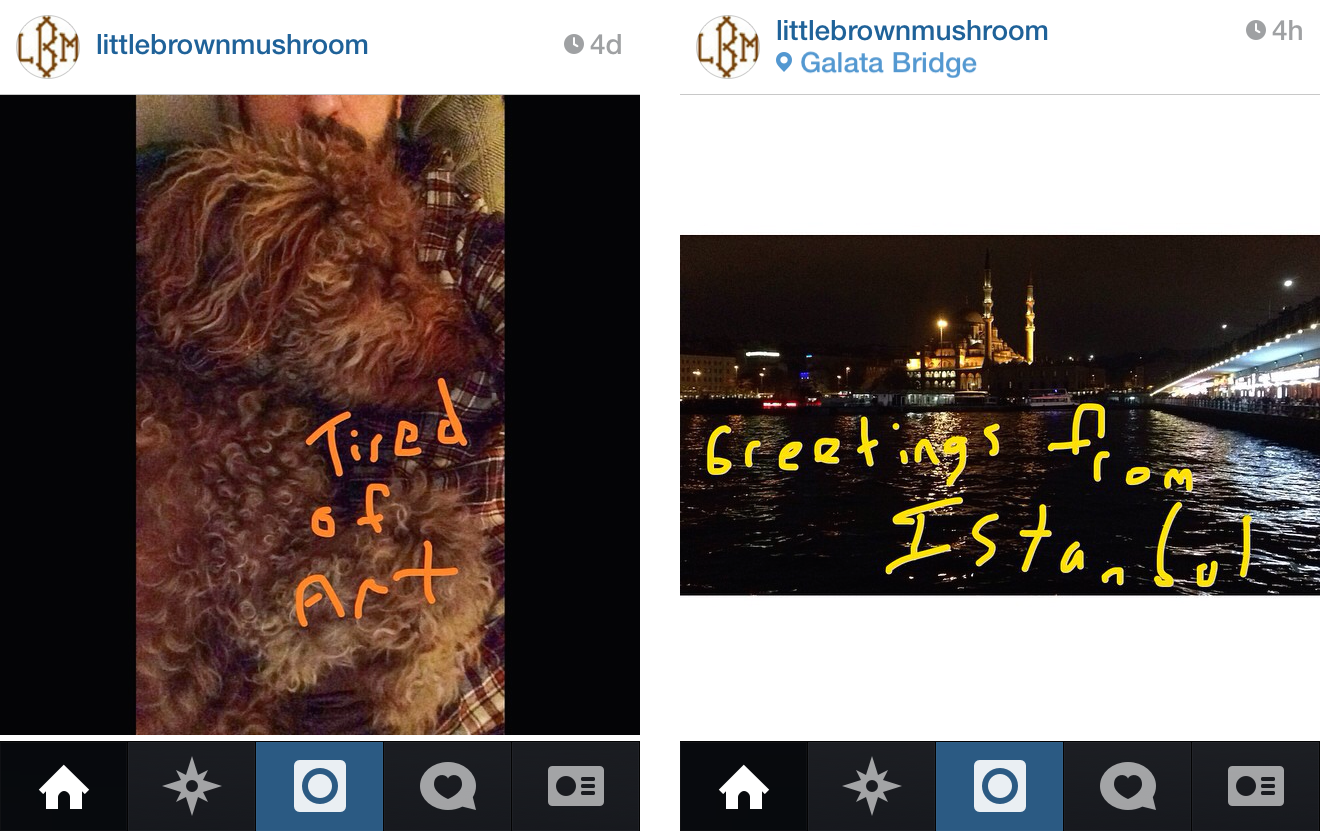

In late 2014 littlebrownmush traveled to Istanbul, where he was involved in printing a book of photographs. Among his artistic interests are Peter Doig and Douglas Huebler, and he enjoys ping pong in the company of Rothko. When he’s tired of art, he lies down with his dog.

Despite the obvious silliness, on some level, of all of this, I couldn’t help but wonder if Soth’s Snapchat biography revealed something about the “real” him. And if it did, how would I know? Had I even accurately remembered the images (or correctly perceived them in the first place)? Would an Instagram biography—publicly archived and cross-verifiable—be better? Are either more or less useful than a typical artist biography? Acting off-script, does a Snapchat biography reveal too much? Or, conversely, does it reveal only what I think I saw?

I can’t say that I know. But I can say that the exercise had the effect of lifting a certain flattening effect of hearing the same story line over and over. And with regular (sometimes daily) infusions of watching Soth work his way through this new form of photographic language, the narrative arc of Soth’s biography that focuses on sheer breadth of visual and material photographic experimentation emerged into prominence. Over the past decade, there have been large format color photographs, of course, but also road-trippy Polaroids, photographs taken with a disposable camera in the language of “bad” photography, projects with found vernacular photographs, a discovery of the languages of Instagram, and a mid-century black and white photojournalism flash aesthetic. Those modes have, subsequently, been funneled into a correspondingly rich range of distribution: fine art books, yes, but also newsprint, pop-up exhibitions, quirky publications, slide shows, posters, billboards, and t-shirts, as well as the more expected prints in museum and gallery exhibitions.

I am hard pressed to think of an artist more fluent through the spectrum of visual languages of 20th century American photography, or who more visibly leverages the movement of multiple forms of photographic images through digital and material spaces, into their consequently contextually contingent meanings. And, this, ultimately, while all the while exploring the capacity and failures of a photograph or photographs to reveal human connections and disconnections.

What I’ve Learned About Photography

It may be obvious to point out that in the accumulations of images seen over time, posted on social media platforms, the ways we can learn about another person are changing. As opposed to still images—that is, photographs that hold still—fleeting photographs register a different temporality both as they are viewed and as they are remembered.

Consciously and regularly engaging with photographic images one knows to be ephemeral necessarily entails both an intellectual and emotional reconfiguration of understanding the value of those images. In both tradition and culture, whether that of the museum or the family photo album, we generally—if unconsciously—understand photographs under a rubric of value that stems from the sustained capacity of those images and objects to deliver a shifting and yet continually relevant meaning to their past, present, and future audiences. Under this rubric, photographic images move forward through time if they can adapt, if they continue to be invested with material, cultural, and emotional value and are seen anew as they move into their futures.

Ephemeral photographs trade on a radically different kind of value, but it’s not no value at all. Rather, it is a value that privileges immediacy and exchange, and the place of accumulative drift in memory as a powerful indicator of future relevance. Like spoken words, which we all intuitively understand to be fleeting (and yet value without question) ephemeral photographs can strike a range of emotional notes: they may be direct, impulsive, lovely, funny, or sweet nothings, they may disappear too quickly or even not quickly enough. These are the ways in which photographs are moving more and more in our contemporary image ecosystem, and rather than write them off as inconsequential or inherently less meaningful than objects that stick around, change hands, are cared for and evolve according to the expectations we hold for them, we can be more attuned to the experiential shifts these other kinds of photographic images have to offer.