Abundant Images and the Collective Sublime

October 1, 2013

Previously published in Exposure 46:2 (Fall 2013), 4-14.

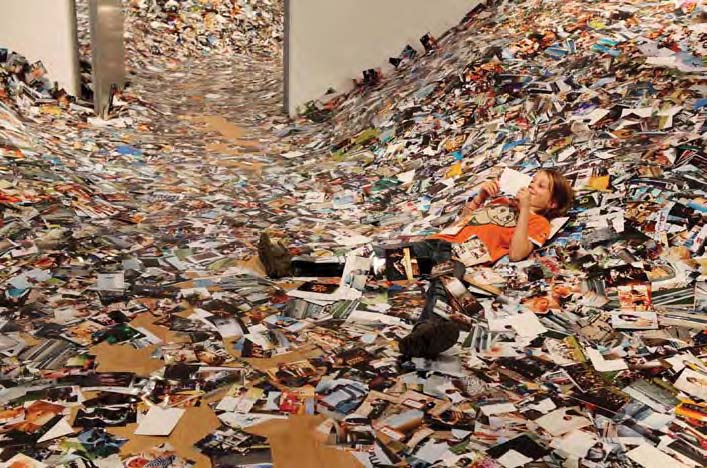

This past November, the Dutch artist Erik Kessels printed out every photograph that was uploaded to the popular photo-sharing website Flickr in a twenty-four-hour period. The resulting installation, appropriately titled “Photography in Abundance,” made literal, both visibly and viscerally, what is in fact only an infinitesimal fraction of the digital photographic images circulating online1 (Figure 1). One day’s haul on Flickr—about a million individual images—is clearly a staggering and incomprehensible quantity of photographs from which to draw a clear meaning. This digital deluge, underway for more than a decade now, has caused considerable hand-wringing among photographers and photography theorists, including concerns about the potential meaninglessness of such a profusion of images, the demise of craftsmanship, and the loss of editing skills within contemporary photographic practice.

But the abundance of imagery in the digital era is also grounds for a critical and aesthetic investigation of how social media and digital technologies enable the making, storage, and distribution of vast quantities of photographic images. From the breadth of this cultural sea change, this essay focuses on artists for whom abundance, quantity, and accumulation present a compelling conceptual challenge, and one, I will argue, that has substantial roots in the pre-digital era. Rather than bemoan the loss of editing skills and the move away from the singular fine photographic print, I will begin with the assumption that volume and accumulation can be their own productive subjects of aesthetic inquiry, ones that are indeed highly relevant to the contemporary photographic discourse. Presenting the viewer with thousands of photographs in an installation, mining online digital photography databases, and referencing social media are some of the strategies artists have employed to engage viewers with the issue of volume in photography.

Abundance, Past and Present

Kessels’s Flickr extravaganza is just one example of several recent photography projects that are predicated on the meaning not of the singular print but on the comprehension—or at least presentation—of staggering quantities of images. His attention to Flickr is not misguided: indeed, the company reports that as of December 2012, more than 8 billion photographs had been uploaded to the site since its launch in 2005, almost eight years ago.2 Flickr is in good company: as of July 2012, Instagram, which launched only in 2010, reported its users had shared 4 billion photographs.3 Yet, both pale in comparison to Facebook, which as of January 2011, reported 200 million photographs uploaded per day, and 90 billion total photographs on its site. For each company, growth has been exponential.4

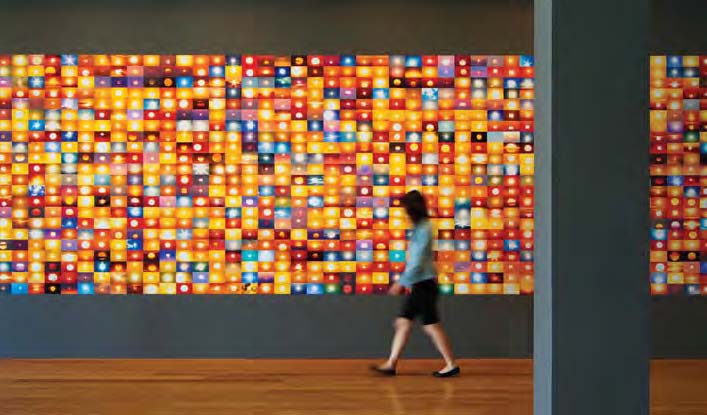

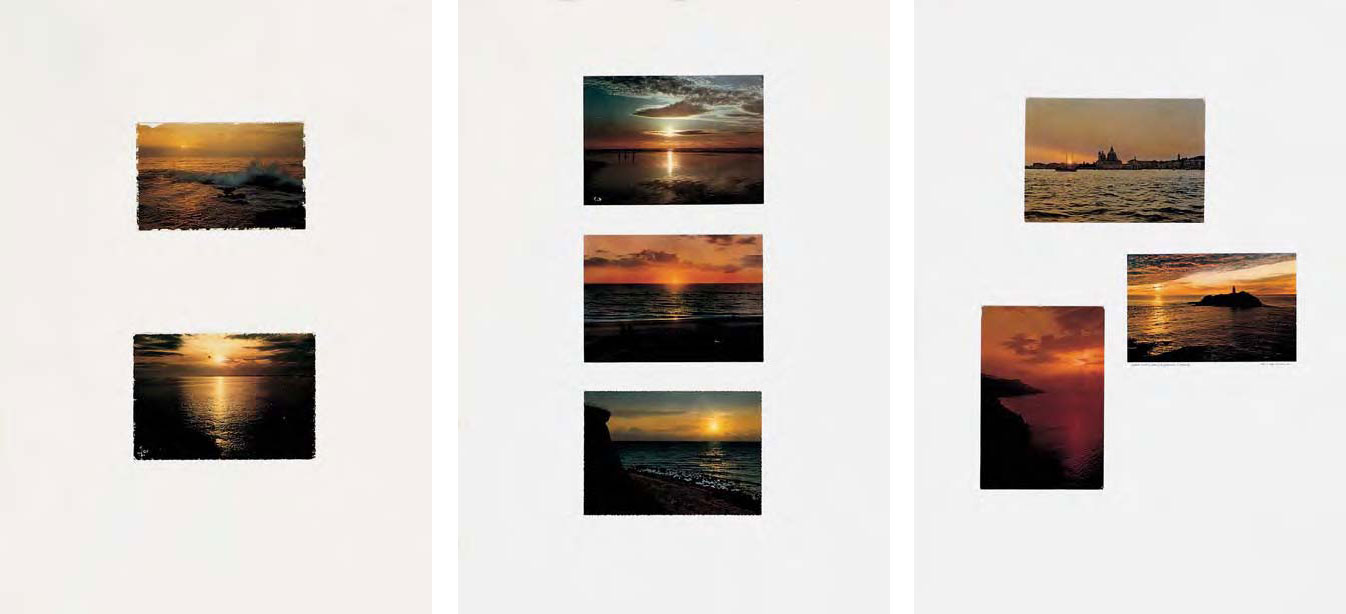

Flickr, in particular, has captured the interest of several artists. Notable among these is Penelope Umbrico, whose popular series Suns from Flickr (Partial), underway since 2006, effectively encapsulates several of the seemingly contradictory aspects of digital abundance and accumulation in the realm of aesthetics (Figure 2). Like Kessels, Umbrico uses Flickr as her source. To create the works, she types the word “sunsets” into the site’s search engine, and culls her imagery from the millions of user-submitted photographs of sunsets. Umbrico does not reproduce the images she chooses in their entirety, but rather, carefully crops them so that the setting sun is the dominant and central feature, and the specificities of particular locations are eliminated. She thus extracts a common core from this collective image database. Umbrico then uploads the images to Kodak’s website, and orders 4 x 6-inch prints online through the company’s EasyShare system.5 Umbrico assembles the small, commercially printed photographs into a grid that typically takes up at least the full scale of a museum or gallery wall, engulfing the viewer in an expanse of sunsets. Ultimately, each individual image is displayed in what emerges as a remarkably tactile installation, given its highly mediated virtual origins. While the installation conveys a sense of sublime endlessness, the few thousand individual images that make it up are really just a small sample of the now more than 10 million sunsets available on Flickr.

The collaborative team of Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe has also worked with the Flickr data stream. Though they also mine the site for images of suns, both rising and setting, their approach is distinctly different than Umbrico’s. Klett and Wolfe’s work is distinct to place, in particular, to the Grand Canyon. Their 2011 piece, One hundred setting suns at the Grand Canyon arranged by hue; pictures from a popular image-sharing web site, measures 82 inches in width (Figure 3). Their process begins in a similar way to Umbrico’s, searching Flickr’s site for particular terms. Yet because of the specificity of location, the project begins to address the artists’ notion of “image density,” tracking locations and views that tourists and visitors to the Grand Canyon repeatedly photograph.6 This image density of a place tells us what people look at and what they choose to record, often in extraordinary numbers. Viewers may already be well aware that the Grand Canyon is one of the most photographed landscapes in the United States, but the project presents the specific photographic views that are made time and again by many different visitors. Wolfe refers to this as “quantifying the sublime,” an idea to which I will return at the end of this essay in a case study of aesthetic approaches to both quantity and sunsets.7

These recent photographic projects indicate a profound shift in how we make, share, and consume photographic images in the twenty-first century, but the aesthetic emphasis on the fact of accumulation and quantity as emblematic of the photographic medium is a pre-digital phenomenon. This is evidenced by the massive storehouses of photographs that exist, including the Smithsonian archive of more than 13 million photographs and the Bettman Archive of 17 million images, to name just two examples. The accumulative impulse is found within fine art photography as well: Garry Winogrand, upon his death, famously left more than 400,000 images he took but never saw.8 Other artists, too, have considered the aesthetics of presenting large volumes of photographic images. Conceptual works by artists such as Douglas Huebler, Hanne Darboven, and Robert Smithson in the late 1960s established the visual and conceptual foundation for today’s cornucopia aesthetic.9

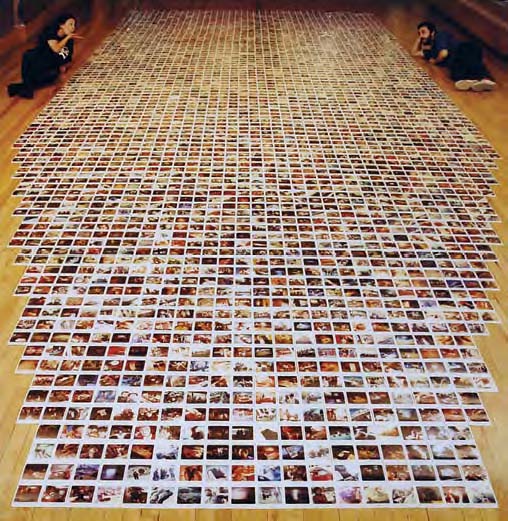

Also, some established modes of photography function, through a gradual accumulation of imagery, as markers of time. In this vein, the gold standard may well be Nicholas Nixon’s extraordinary series The Brown Sisters, a suite of annual portraits made since 1975 of his wife and her sisters. The work, still in progress, consists of thirty-eight portraits of the sisters documenting their relationship for as many years.10 Four years after Nixon began his project, the photographer Jamie Livingston began another time-based project, with starkly different aesthetic results (Figures 4 and 5). In 1979, he began to take one Polaroid photograph per day, recording an accumulation of moments that ultimately spanned eighteen years. The project ended upon Livingston’s death in 1997, composed of 6,697 Polaroids, dated in sequence.11 Despite its longevity, The Brown Sisters, photographed annually, exists within the fine print tradition, each year’s portrait adding to the project’s contemplative and poignant regard for the passage of time. Livingston’s project, by contrast, speaks to photography as a medium both of voracious consumptive and accumulative tendencies, and though it is marked by a far higher degree of repetition throughout its imagery and a far lesser degree of craftsmanship, it is no less poignant a cumulative document.12

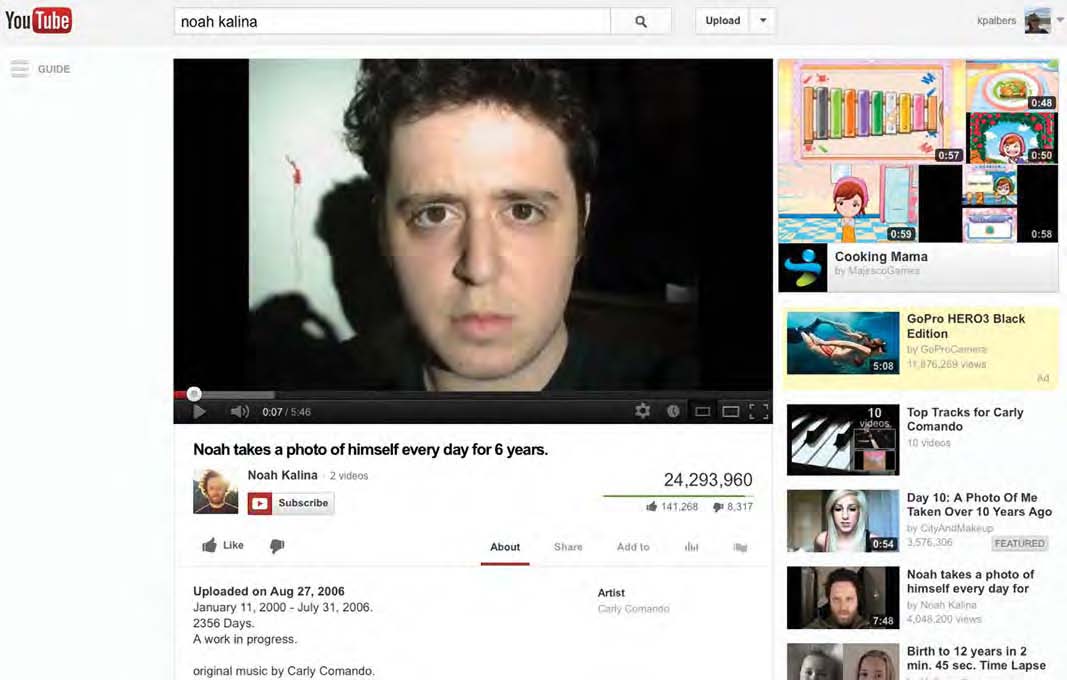

One can wonder what Livingston’s project would have looked like in the digital age.13 There is no question, however, that digital photography now makes accessible to a far broader spectrum of photographers the kind of photographic accumulation that once was isolated to somewhat unusual cases such as Garry Winogrand or Jamie Livingston. To accumulate even tens of thousands of photographs fazes no one. But the impulse to obsessively mark time via photography is enabled in a new way, with yet again different, and decidedly more mundane, aesthetics. Starting thirteen years ago, on January 11, 2000, Noah Kalina began making a digital picture of himself every day: his video, tracking six years of progress and 2,356 images, is a viral hit on YouTube, having been seen more than 24 million times14 (Figure 6). Notably, the aesthetics of presentation have shifted. Nixon’s thirty-some gelatin silver prints require at least a large wall to exhibit, and Livingston’s 6,000 Polaroids required 120 linear feet of exhibition space, with the small prints arranged frameless and touching one another, stacked seven feet high. Kalina’s project, by contrast, exists only digitally and is presented as a time-lapse sequence on a monitor. Though his work is certainly seen most often as a YouTube video, Kalina has also presented it on a freestanding video screen in a gallery space.15

As cultural observers begin to catalogue the aesthetic strategies of presenting such accumulation, it is worth noting that according to rapidly shifting data storage standards, even Kalina’s obsessiveness is relatively mild. Every individual’s capacity to self-archive is rapidly expanding in our digital age. In 1999, for example, computer scientist Dr. Gordon Bell began to archive his own life, correspondingly designing the technology that allowed him, and the world, to do so.16 Bell gathered emails and family photos, tracked phone calls made and web pages visited, and digitally stored memos, health records, home movies, voice recordings, and books. No detail was too mundane: he saved canceled checks, peeled off and scanned the labels of the bottles of wine he drank, and archived his airline boarding passes with the care typically reserved for precious family photographs. Bell was the experimental subject of Microsoft’s MyLifeBits program, the goal of which is to develop the technology to produce a personal archiving program that is, as the company puts it, “a lifetime store of everything.” Bell’s project is emblematic of an age in which the human desire to keep cherished mementoes from the past intersects with extraordinary and agile storage technologies. Indeed, a prototype for a new life-logging camera was just released by the Swedish company Memoto, which automatically records one photograph every 30 seconds around the clock. While hung around the life-logger’s neck or attached to his or her clothes, the camera can record 1.5 terabytes of geotagged visual data over the course of a year. The company cheerfully claims that the device will “give you pictures of every single moment of your life,” adding, “This means that you can revisit any moment of your past.”17

Case Studies: Suns

Many more photographic examples could be cited here, yet the selection I have introduced highlights a range of both artistic and cultural practices of image production in a time of great accumulative possibility. The rest of this essay outlines a series of case studies—both pre-digital and digital—of artists whose work addresses accumulation and volume in photography practice, considering the intellectual and organizational structures through which everyday users of photography make meaning from such volume, from historical atlases to digital databases.

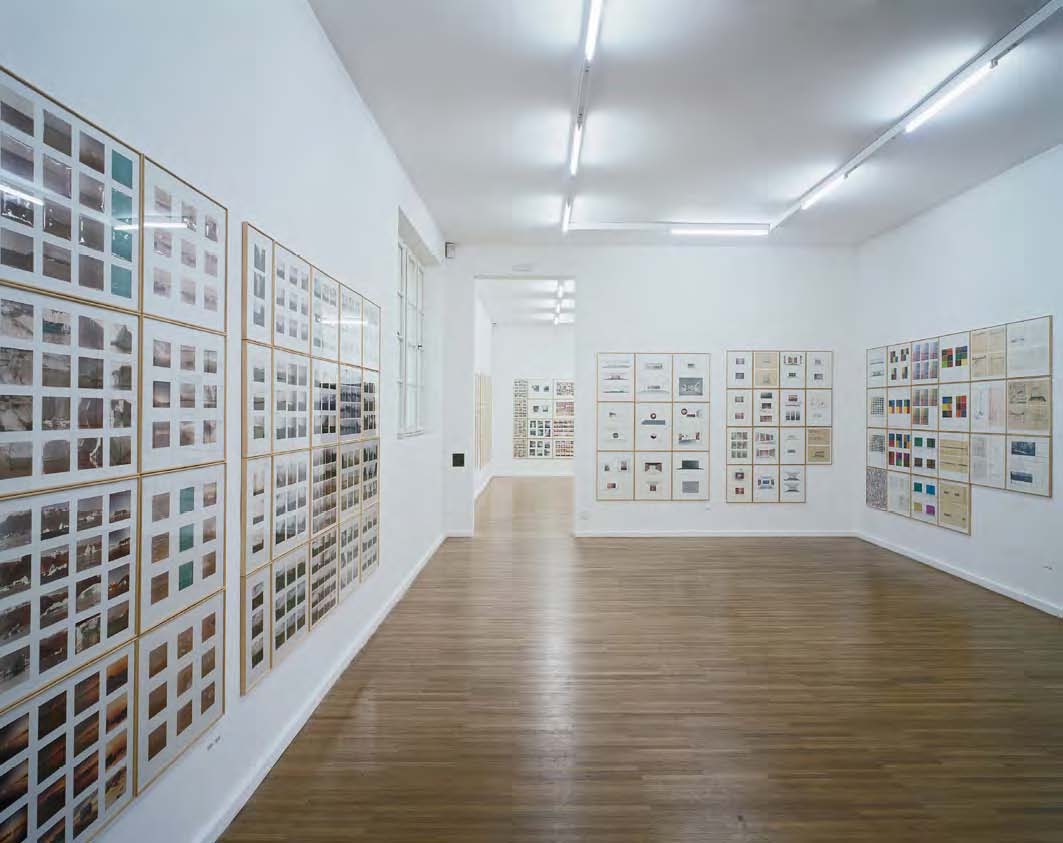

German artist Gerhard Richter’s massive and ongoing Atlas—a now monumental work that was first exhibited in 1972 with a “mere” few thousand photographic images—is a cornerstone of accumulative aesthetic and photographic practices. Some forty years in the making, Atlas is now composed of upwards of 8,000 individual images: a number that, while admittedly a far cry from Kessels’s one million images, still evinces volume on a scale that resists easy consumption or interpretation (Figures 7 and 8).

The content of Atlas interweaves both a personal history and a larger political history, incorporating fragments of national and international events with personal family snapshots, as well as images from the artist’s professional work, in the form of sketches, proposals, and source photographs for many of his paintings. Atlas begins with hundreds of family photographs and mass media images, and moves on quickly to encompass images from a broader political world. But throughout, and often for long stretches at a time, Atlas is strikingly banal, offering up hundreds of photographs the artist took and had commercially printed of landscape, scenery, domestic life, and even sunsets. Viewers see places, such as Sils Maria, that Richter visits frequently, and intimate photographs of his wife, Sabine, and the birth and babyhood of his children, Moritz and Ella. Additional photographs of Richter’s friends and acquaintances, the artist’s home, trains, flowers, architectural studies, and other ephemera are included, among much more.

Scholarship on the spatial dimensions of Richter’s Atlas has focused on the whole, digesting the generalizations of groups of images rather than dissecting the particularities and specificities of individual photographs within the panels. To a large degree, this is simply a practical critical response to such a massive undertaking. Faced with upwards of 8,000 individual images in Atlas, a minimum of three and a half hours are necessary to look at each individual image for a mere two seconds.

The structure of Atlas, both in name and in mechanics, allows viewers to dwell on the important differences between ways of assembling knowledge. An atlas is different from a database, a repository, an archive, an album, or any other number of accumulative arrangements. Atlases—whether in the sciences or in terms of maps—are compendiums of knowledge in any given area or field. Indeed, the very category “atlas” directs the reader to a particular consumption of Atlas’s peculiar accumulations. While an album is a well-recognized and understood form, and archives have been the subject of intense artistic, curatorial, and scholarly inquiry for more than a decade now, the atlas genre is less distinct. To complicate matters, Richter’s Atlas has most often been analyzed as a kind of archive, albeit a very public one.18

Art historian Dorothea Dietrich, however, has gone farthest in reading Atlas as, actually, an atlas. An atlas, Dietrich writes,

is an instrument of control … [in which] the unfamiliar is brought under control by the ordering eye and hand of the cartographer, the distant territory neatly charted and represented in readable form as a two-dimensional abstraction. It holds at bay the terror of the unknown and is relentless in its pursuit of order. Its agenda is all-encompassing, its goal the charting of each and every area of the globe so that even the last remaining pocket of chaos will be tamed and made available as ordered space. And once the space has been charted and the map drawn … the atlas may become the road map for the developer.19

Dietrich puts Richter in the role of the controlling cartographer charting his territory, holding the unknown at bay, pursuing order, and taming chaos. In this view, Richter is in a clear position of power, deftly organizing his barrage of otherwise unwieldy photographic imagery—and personal history—into a controlled area, fit for presentation, much like a mapmaker. Far from neutral, atlases of maps have always been constructed to communicate and circulate a specific world-view through their particular spatial arrangement of visual information. The atlas-maker’s job is to assemble a view of the world from the best available sources: an atlas seeks to create a whole greater than the sum of its parts.20

Historians of science Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison recount that it was by the eighteenth century that the term atlas came to designate not just illustrated volumes of geography—maps—but also astronomy and anatomy. By the nineteenth century, these picture books were produced as guides throughout the empirical sciences, covering topics as varied as snowflakes, diseased organs, clouds, and crystal structures.21 These atlases, whatever the field, purport to be a totalizing view, the final word on any given subject. Atlases both define and claim knowledge of discrete subjects, whether that subject is topography or botany or world history. Atlases, Daston and Galison write, “are the guides all practitioners consult time and time again to find out what is worth looking at, how it looks, and, perhaps most important of all, how it should be looked at.”22 They are made to instruct, expected to do no less than teach us to see. Looking at Richter’s Atlas in fact, then, as an atlas, yields an understanding of his project within a specific cultural structure, and as one that guides us, as the viewers, to understand its wide-ranging accumulations as a complex editorial venture—far from the neutrality any “archive” might suggest.

The Flickering Sun

What do Richter’s pre-digital accumulations have to do with their digital counterparts? Where might Atlas find continuity within the digital realm, and where does it diverge? In order to address these questions, I will look at Richter’s many photographs of sunsets contained within Atlas, reading them alongside Penelope Umbrico’s Suns from Flickr and Klett and Wolfe’s Grand Canyon suns. Both projects move away from the structural specificities of the atlas form and insist instead on a consideration of more current accumulative apparatus: the digital archive, database, and image stream.

From as early as 1969, Richter collected postcards of sunsets. He has continued to add his own commercially printed photographs of sunsets to Atlas over the ensuing decades.23 While a few images in Atlas do stand out, the sunsets do not. Rather than grabbing a viewer’s attention, they more typically fade into the march of more or less routine landscape photographs that characterize much of Atlas, repeating, for the viewer, the experience of looking at someone else’s pretty vacation pictures. And, at least in the early iterations of Atlas sunsets, Richter is mining a kind of pre-digital data stream: choosing images that already exist in the world. That recycling of images marks a distinctly different working process than the majority of the work discussed thus far. Whether working with fine gelatin silver prints, Polaroids, or digital capture, Nicholas Nixon, Jamie Livingston, and Noah Kalina each produce their own photographs. However, Atlas’s early tendency to dwell on the already-photographed is picked up in the database-mining of Umbrico, Kessels, and Klett/Wolfe.

Penelope Umbrico’s anonymous sunsets in Suns from Flickr are more distinctly depersonalized than those in Atlas, but as a result are more easily read as emblematic of a universal experience. The effect of Umbrico’s installation depends on its materiality: despite each individual photograph’s digital origins, the visual experience of seeing a wall full of sunsets is aesthetically closer to the presentation of Livingston’s daily photographic project or to Richter’s Atlas than the video monitor presentation of Kalina’s years of self-portraiture. Its accumulations are viscerally felt: the viewer can soak up a field of sunsets en masse.24 The sameness of Umbrico’s sunsets is due in large part to her choice to crop and, thus, generalize the visual information. Whatever the source of the original images, Umbrico’s editing of them creates a homogenized visual totality that thwarts any comparison of these many iterations of the sun. Despite her editorial hand, then, Suns from Flickr refers much more pointedly than any image in Atlas to collective photographic production.

Umbrico resists calling her sunsets an archive, saying that the piece “uses an archive (all the sunset pictures on Flickr) which is made up of data … as the means (not an end) to make art.”25 But, as with Richter’s Atlas, the categorical tension between her accumulations and a known cultural structure—Flickr—proves productive, provoking an analysis of the archival qualities of the Internet. Both photography and the Internet, Umbrico suggests, “function as indexical records of our collective culture—a visual index of data that represents us: a constantly changing and spontaneous auto-portrait.”26 Unlike Richter’s sunsets, operating as the product of one individual’s thought process, Umbrico’s sunsets engage the implications of an anonymous social and technological collective of accumulation. What may have started as a deeply personal moment—the contemplation of a sunset—becomes, as the experience is photographed and subsequently uploaded to Flickr, a participation in a decidedly routine collective cultural ritual. As Umbrico has noted, photographing sunsets, “is something we all engage in, despite our better artistic judgment, knowing that there have been millions before and there will be millions after.”27

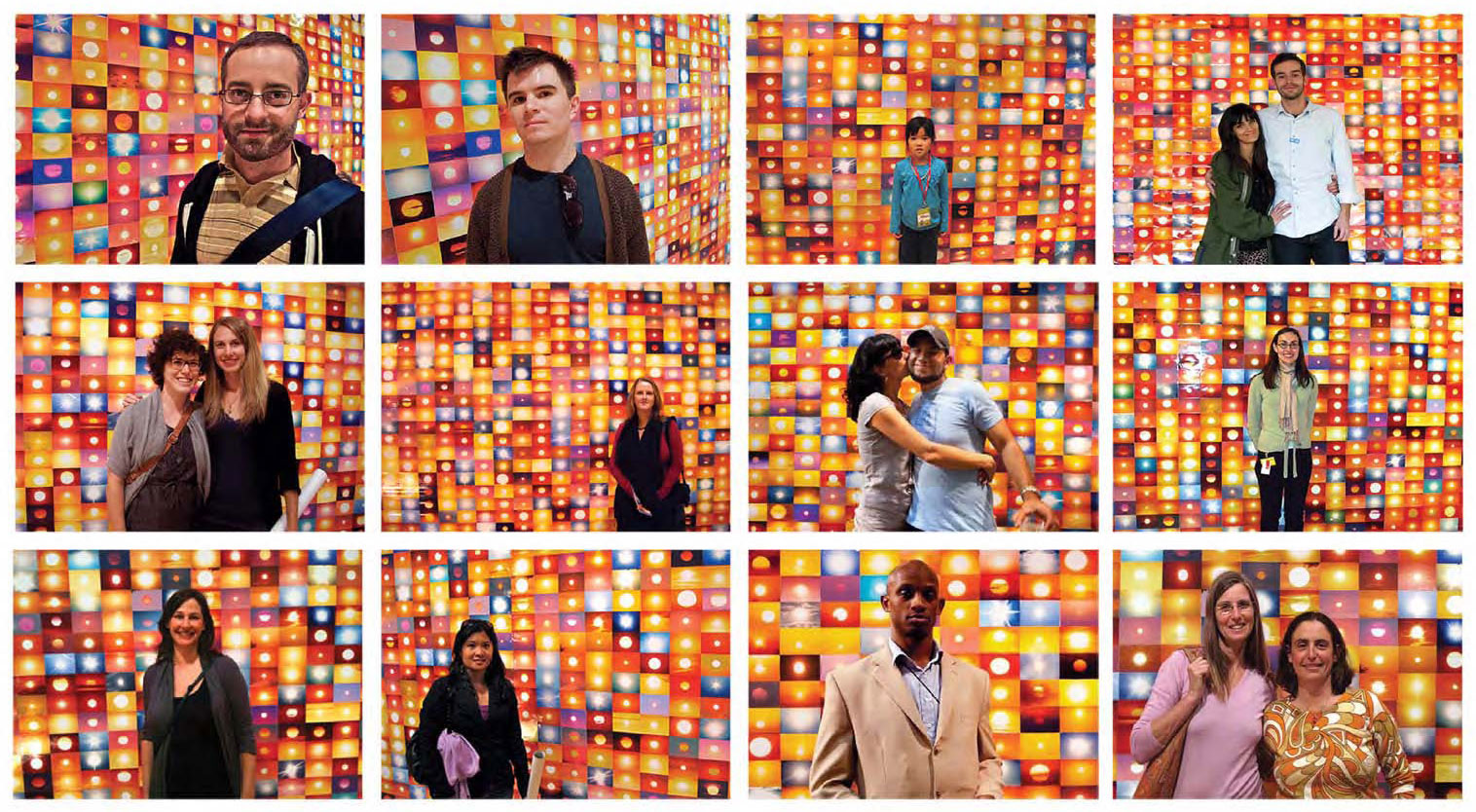

While Richter’s Atlas can be off-putting to its viewers, appearing in installation as an imposing and overwhelming edifice that is difficult to access, Umbrico’s sunsets have proven to be decidedly user-friendly. In a fantastic display of aesthetic circularity, viewers routinely photograph themselves in front of this panoply of sunsets, almost as they would a real sunset. Better yet, they upload these photographs back onto Flickr, and Umbrico finds them, prints them out, and arranges them in an installation titled People in front of Suns (From Sunsets) from Flickr, just as she does with the “original” suns (Figure 9). One appeal of having one’s picture taken in front of Umbrico’s Suns from Flickr is, as the artist suggests, “a similar physiological response to the visual warmth of the images that is analogous to the actual warmth of the sun.”28 In other words, her installation makes viewers feel good. To this I can testify. When I encountered Umbrico’s installation at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, I joined a cohort of happy lingerers milling about and collectively basking in the warmth of the piece. My husband photographed the installation himself and used the image as the wallpaper on his iPhone for a couple of years—a way, I suppose, of getting away with having a corny sunset image as a screensaver that reads nevertheless as art.

Another point of appeal with Umbrico’s Suns from Flickr installation may be that we recognize ourselves, or a memory of ourselves, and feel invited to re-perform the collective ritual of posing in an echo of what we have done before. In this way, Suns from Flickr is distinctly un-atlas-like. It does not address us from a position of authority, presenting us with a body of knowledge and teaching us to see. Rather, it brings us back to our comforting mediated rituals, pointing out, perhaps, the un-originality of photographing a sunset, but ultimately affirming our own participation in the collective practice.

The role of collective ritual appears as well in Klett and Wolfe’s Flickr investigations of the Grand Canyon. The image I began with, One hundred setting suns at the Grand Canyon arranged by hue; pictures from a popular image-sharing web site, 2011, differs in presentation from both Richter’s and Umbrico’s sunsets: the cropped Flickr images are arranged by hue and then recombined into one digital file and produced as a single (albeit very large) print. In this aesthetic, the physicality of the individual prints is elided in favor of a uniform visual presentation.

The artists’ long-term collaboration has grown out of their work in the realms of re-photography, and years worth of literally re-tracing the footsteps of photographers who had come before them.29 The Flickr work is a clear departure from their established practice of a precise and historically based view of the contemporary landscape. And yet, at the same time, Klett and Wolfe continue to investigate the views of other photographers, but rather than following Timothy O’Sullivan or Ansel Adams, their guides are the legions of amateur photographers who have shared their work on Flickr. And it is the collective ritual of these visitors to photograph the canyon that provides Klett and Wolfe with a repository of views of this particular and deeply iconic place. Wolfe has referred to their practice as “quantifying the sublime,” which strikes me as a concept precariously balanced on the brink between sincerity and cynicism.30 Indeed, camera-toting tourists are an easy and fun target for critics, seemingly mindlessly recording the same obligatory souvenir shots, over and over. They are suspect of not really seeing a place and thus, by extension, not really experiencing it.31 But Klett and Wolfe’s project is not cynical, rather it is deeply human: an investigation that recognizes and appreciates, rather than mocks, the routine viewing and photographic habits of Grand Canyon visitors.

The artists’ interest in the idea of image density—of quantifying how many photographs have been made of a particular view—in fact began with an interest in how many photographs had been made from particular locations. That is to say, Klett and Wolfe first began with the problem of how to visualize where photographers had stood (and they made topographic studies of photographic viewpoints in Yosemite in this regard) but evolved into the problem of how to visualize what people had looked at most and where they pointed their cameras.32 Their conceptual way of approaching Flickr, then, differed markedly from Umbrico, whose sunsets are of anyplace, recording the broad propensity of people to take a photograph of the setting sun no matter where they are, until every specific sunset becomes a totality of the concept “sunset.”

A second piece by Klett and Wolfe, Fifty sunrises at Mather Point arranged by a shared horizon; pictures from a popular image-sharing web site, 2011, gets at this point more directly (Figure 10). In this case, Wolfe mined Flickr for literally overlapping photographs of the same site and graphed them onto one another in a kind of “average” view of a Grand Canyon sunrise. By lining up familiar topographic features and adjusting the opacity of the overlaid images, Wolfe could virtually “stand,” from the comfort of his home in northern California, where the fifty Flickr photographers had stood to watch the sunset. Unknown family members and friends appear as ghostly forms, their images not quite strong enough in the composite layering of separate photographs to be recorded for posterity in this iteration. Nevertheless, their forms humanize the Grand Canyon pilgrimage, the ritual of rising early to watch the sunrise, and its subsequent photographic capture.

To end where we began, Erik Kessels’s response to the volume of photographic imagery available on Flickr seems to be the equivalent of throwing his hands up in the air and declaring a kind of hedonistic defeat: none of us stands a chance in this deluge, the best we can do is roll with it, gorging ourselves on the overload of imagery. Despite its radically different temperamental and aesthetic sensibility, this approach has something in common with the pre-digital accumulative idiosyncracies of Richter’s Atlas, in which the artist collects a tremendous range and variety of photographic imagery, but resists producing a narrative. Umbrico and Klett/Wolfe’s projects function more as core samples, forgoing any attempt at capturing range in favor of dwelling on the same subject, seen again and again, either from vantage points around the world, or vantage points within a few feet of one another. As such, instead of documenting the accumulations of a single individual, they tap into shared photographic experience (and, via Flickr, shared experience shared).

Umbrico has underscored the exponential growth of Flickr by changing the numbers in the titles through the ongoing installations of her work. In 2007, the title was 2,303,057 Suns from Flickr (Partial) 09/25/07. In 2008, it was 3,221,717 Suns from Flickr (Partial) 03/31/08. By 2011, it was 8,730,221 Suns from Flickr (Partial) 02/20/11. Ultimately, it doesn’t really seem to matter whether there are 2 million or 8 million suns on Flickr, whether the Smithsonian archives 10 million or 13 million photographs, or how quickly Instagram will surpass the 5 billion image mark. In this scenario, where the singular print might seem to be beside the point, not even part of the equation, in fact each and every sunset photograph becomes emblematic of the whole, of the entirety of 8 million sunsets: cosmic rather than banal. The artist’s intervention is finite; even Flickr, in its boundlessness, is finite. One photograph is no match for the relentlessness of the totality of the photographic enterprise or for the experience everyone wants to capture: day after day the sun comes up and the sun goes down. And yet, each photograph is a microcosm of this endlessness. Whether or not Umbrico continues to add installations to the ever-growing accumulations of sunsets on Flickr, people will continue to photograph and share their photographs of sunsets without her, just as they will continue to rise before dawn at the Grand Canyon, capturing their ghostly figures at sunrise to share with friends and family. The sublime marches on.

Notes

-

The piece was installed at the FOAM exhibition The Future of the Photography Museum, in Amsterdam, November 5 to December 7, 2011. ↩

-

Matt Brian, “8 Billion photos later, Flickr finally gets a new look” The Next Web, December 12, 2012, http://thenextweb.com/insider/2012/12/12/8-billion-photos-later-flickr-finally-gets-a-new-look/ (accessed March 31, 2013). ↩

-

Emil Protalinski, “Instagram passes 80 million users,” C-Net, July 26, 2012, http://news.cnet.com/8301-1023_3-57480931-93/instagram-passes-80-million-users/ (accessed March 31, 2013). Recent data (January 2013) reports that Instagram users post 40 million photographs per day. Rebecca Greenfield, “How Many Users Does Instagram Really Have after the Ad Scandal?” The Atlantic Wire, January 12, 2013, http://www.theatlanticwire.com/technology/2013/01/how-many-users-does-instagram-have/61139/ (accessed March 31, 2013). ↩

-

According to Facebook engineer Justin Mitchell on the company blog, January 25, 2011, https://blog.facebook.com/. It is worth noting that Facebook bought Instagram in 2012 for about $1 billion. ↩

-

Penelope Umbrico, email correspondence with the author, November 22, 2011, to February 12, 2012. ↩

-

See Rebecca A. Senf’s essay in Klett and Wolfe’s recent publication, Reconstructing the View, for a discussion of image density with regard to the artists’ broader oeuvre and its implications as a replacement for “then and now” picture pairs. Senf also details the crucial position of online database searches in their Grand Canyon work particularly as it pertains to research on prints made by individual photographers within a fine art or commercial history. Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Reconstructing the View: The Grand Canyon Photographs of Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe (Berkeley: University of California, Press, 2012). ↩

-

Byron Wolfe, in telephone interview with the author, November 28, 2012. ↩

-

Winogrand left more than 2,500 rolls of undeveloped film, 6,500 rolls of processed film, and 3,000 rolls of contact sheets that evidently had not been looked at: a total of 12,000 rolls, or 432,000 photos. His archive is held at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, AZ. See John Szarkowski, Winogrand: Figments from the Real World (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1988). ↩

-

I am thinking of Hanne Darboven’s Kulturgeschichte 1880–1983; Douglas Huebler’s Duration Pieces, in which he claimed to be trying to photograph “everyone alive”; and Robert Smithson’s now-lost 400 Seattle Horizons, 1969, in which he sent Lucy Lippard instructions for a work consisting of 400 photographs to be taken of deserted Seattle horizons with a Kodak Instamatic camera. ↩

-

The series has been published twice in full, most recently in Nicholas Nixon, The Brown Sisters: Thirty-Three Years (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2007). ↩

-

The entire group of Polaroids was shown in the exhibition Photo of the Day: 1979–1997, 6,697 Polaroids, Dated in Sequence at Bertelsmann Campus Center at Bard College, New York, in 2007. See David Shaftel, “The Days of His Life,” The New York Times, October 10, 2008. Figure 4, illustrated here, shows Jamie Livingston on the left and his girlfriend Betsy Reid on the right. According to Hugh Crawford, Livingston intended the exhibition to be titled Some Photos of That Day: 1979–1997, 6,697 Polaroids, Dated in Sequence. I am grateful to Hugh Crawford for his email correspondence with me about this work. hugh@hughcrawford.com ↩

-

Many more projects could be discussed in this context including Andy Warhol’s massive quantities of Polaroids and snapshots; Nancy Floyd’s daily self-portraits in her project Weathering Time (1982–present); Karl Baden’s daily self-portraits Every Day (1987–present); Suzanne Szucs’s daily Polaroids, Journal, In Progress (1994–2009); Roni Horn’s 100 portraits of the same woman in You Are the Weather Part I (1994–1996) and Part II (2010–2011); Alfredo Jaar’s 100 Times Nguyen (1996); and Betsy Schneider’s daily portraits of her daughter in Quotidian (1997–2009). ↩

-

The practice has moved well beyond a practice within a fine art context, indeed Flickr now has several groups dedicated to so-called “365” projects in which participants take one photograph every day of the year in subgroups from self-portraits to pictures “around the house,” and daily photographs of beloved pets to iPhone-specific users. To date, the 365 Flickr pool has more than 21,000 members and more than 1 million photographs. ↩

-

In September 2012, Kalina posted an updated video of 4,514 photographs, tracking 121⁄2 years. As of November 2012, it has been seen more than 4 million times, for a total of more than 28 million views of both videos. ↩

-

www.noahkalina.com (accessed April 1, 2013). ↩

-

See Microsoft’s research page, http://research.microsoft.com/en-us/projects/mylifebits/ (accessed April 1, 2013). ↩

-

See www.memoto.com (accessed April 1, 2013). It is curious that even with the extraordinary volume of data that actually is recorded, the company still feels the need to exaggerate the claim for “every single moment” and “any moment” from your past. A darker side to the commercial optimism of the MyLifeBits and Memoto projects is seen in the work of Bangladeshi-born American artist Hasan Elahi and the Iraqi-American artist Wafaa Bilal. Mistakenly added to the U.S. government’s terrorist watch list in 2002, Elahi has since digitally self-tracked and archived the minutia of his own daily comings and goings. Elahi takes up to 100 digital photographs a day as a record of his meals, his locations, and his encounters, and uploads them to his website, TrackingTransience.net, making them available for anyone—including the FBI—to view. A GPS device continuously tracks his location, and the information is available in real time on his website. Bilal made a more extreme entry into self-surveillance by having a digital camera surgically implanted in the back of his head, which is programmed to take one photograph a minute. The camera was in place for one year, 2010 to 2011. Its images were livestreamed, along with geocoordinates, to Bilal’s website, 3rdi.com, where ultimately more than 500,000 time- and location-stamped photographs were archived. ↩

-

Arguably the most prominent and authoritative reading of Atlas is Benjamin Buchloh’s, from his 1999 article “The Anomic Archive.” Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, “Gerhard Richter’s Atlas: The Anomic Archive,” October 88 (Spring 1999): 117–45. I have elaborated on the structure of Atlas in my article “Reading the World Trade Center in Gerhard Richter’s Atlas,” Art History 35:1 (February 2011): 152–73. ↩

-

Dorothea Dietrich, “Gerhard Richter’s ‘Atlas’: One-Man Show in a Shipping Crate,” The Print Collector’s Newsletter XXVI, no. 6 (January–February 1996): 204. ↩

-

Ibid., 26. ↩

-

Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, Objectivity (New York: Zone Books, 2007), 23. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Though he has not, to my knowledge, painted a sunset. ↩

-

The layout and design of Umbrico’s recent monograph, which functions effectively as an artist’s book in this regard, achieves a transposition of this visual effect. Penelope Umbrico, Penelope Umbrico (photographs) (New York: Aperture, 2011). ↩

-

Penelope Umbrico, email message to author, February 1, 2012. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Penelope Umbrico, email message to author, February 11, 2012. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

For a discussion of their working process, see especially Rebecca A. Senf, “Reconstructing the View: An Illustrated Guide to Process and Method,” in Klett and Wolfe, Reconstructing the View. ↩

-

Byron Wolfe, in telephone interview with the author, November 28, 2012. ↩

-

An early critique of tourists’ unthinking reiteration of famous shots they have seen before can be found in Pierre Bourdieu’s Photography: A Middle-Brow Art, trans. Shaun Whiteside (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990), originally published in French as Un art moyen: essai sur les usages sociaux de la photographie in 1965. Variations of the critique are widespread: Susan Sontag took it up in her essays from the 1970s compiled in On Photography (New York: Anchor Books, 1989); the protagonist in Don DeLillo’s novel White Noise (New York: Viking Press, 1985) visits the most photographed barn in America and meditates on the impossibility of any longer seeing the barn itself. ↩

-

Byron Wolfe, in telephone interview with the author, November 28, 2012. ↩