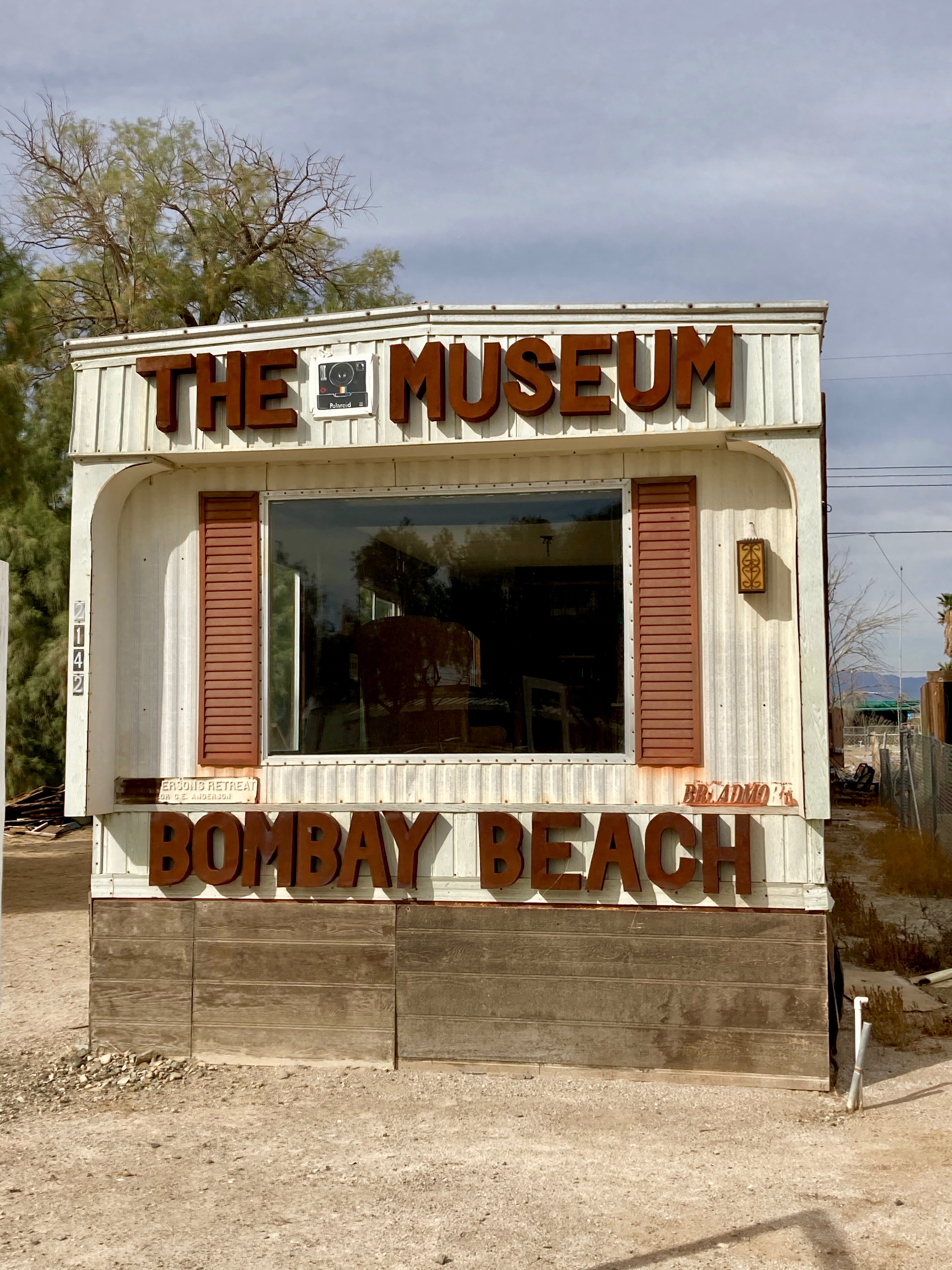

Polaroids at Bombay Beach

February 20, 2021

I have a soft spot for aspirationally-named museums that have very little to do with conventional museums, and another soft spot for art that I accidentally come across in unexpected places and ways, and yet another soft spot for art that is falling apart. So, in hindsight it’s not too surprising that my jaw dropped in gradual realization as I slowly put together, while moving through it, that not only had I come across an abandoned installation of Polaroid photographs in a surreal shell of a town, but that that decaying set of rooms and pictures was in fact called The Polaroid Museum of Bombay Beach: a single-wide trailer, (formerly) resplendent in 1960s shag and wood-veneer paneled décor, open to the elements, the site of a temporary exhibition dedicated to that most temporally engaging form of analog photography: the Polaroid.

But none of this was evident at the outset of my accidental visit. Bombay Beach sits on the east shore of the Salton Sea, an inland body of water that is the largest in California measured by surface area (Lake Tahoe has more volume) and has been slowly evaporating since its formation in 1905, when a canal broke and the lake accidentally filled the Salton Trough. Now for over a century, it has sat 227 feet below sea level, with no natural outlet. That broader context is unusual enough: the immediate region itself is in a constant state of physical decay as the impacts of the receding shoreline exposes more and more dusty playa, rich with toxic agricultural run-off.

The town of Bombay Beach saw its heyday in the 1950s, a popular recreational retreat from Los Angeles that rivaled Palm Springs, attracting visitors with water skiing, boating, and beach-going. By the late 1970s and 80s, it was already in steep decline, with recent floods having left parts of the town submerged. The 2020 census registered some 400 residents, and the last decade has seen a persistent uptick in artists and filmmakers visiting, some to participate, since 2016, in the Bombay Beach Biennial (held annually, curiously enough). The last Biennial,though, was in 2019; the 2020 and 2021 editions have been postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Most descriptions of Bombay Beach are casually comfortable with the term post-apocalyptic as a useful adjective to evoke the place and its feeling. Surprisingly, the current population of 400 reflects a marked growth in human habitation over the last decade. But visiting for the first time nearly one year into the pandemic, in the especially hard-hit region of the Imperial Valley (east and inland of the similarly hard-hit Los Angeles), everything felt pretty desolate. That I hadn’t planned ahead, was a bit short on time, and happened to drive by the Museum on my way out, made the visit all the more disorienting.

It’s not totally clear, to a visitor, if the Polaroid Museum is permanently open, or permanently closed. The weekend-long festival of its origin ended nearly two years ago, but it seems, in this case, like the front door has been open, literally, since then. The trailer site is bleak and dusty, but, once I crossed the yard and went up the steps, a small sign confirmed that this was an art show, and I began to feeI I (probably) wasn’t trespassing. Poking a head through the door, one sees that thick shag rug, and old armchair, a small TV strewn on the floor, ratty walls and a rusty—though clearly formerly well-kept—efficiency kitchen. And, Polaroid photographs. A large one by the armchair, others around the room, accompanied by placards about each artist.

The exhibit was put together by a German-born artist, Stephanie Schneider, and featured an array of international artists who, like her, were drawn to the fleeting and unpredictable nature of (often expired) Polaroid film, or its more recent off-brand reboots. The aesthetic allure of the largely expired original Polaroid films are at the heart of these artists’ interests, as is the physical and time-based experience newer versions of “instant” film still offer. And, it worth noting, many prints in the installation are enlarged, digital versions made from original unique instant prints.

The trailer seemed to have fallen into disrepair long before, but from a state of lively décor. The passage of time inside was hard to gauge. One photograph, of a young woman with blond bouffant hair who seemed to be nearly vanishing into the patterning of her bedcovers and the lush and verdant wallpaper behind her was, itself, further camouflaged by the stove’s decorative floral backsplash. Down the narrow hallway leading away from the main room—and stepping gingerly over rotten floorboards—this visual play of color and pattern between photographs and the actually-decaying wallpaper, original to the trailer, continued: an elaborate blue and gold bathroom wallpaper the new stage set for a gold glittered and dreamlike image.

Aside from the decorative play of layering overtly theatrical photographs atop decayed baroque patterns—one fraying temporal experience literally overlaying another—what struck me most of all was all the missing photographs. Apparently stolen over the years, the walls bore the stripped marks of forcible removal: the photographs hadn’t been hung, but affixed to the walls’ paneling, and when they were taken, it showed. Despite the many missing images—and one can see from the remaining illustrated labels which objects appealed to perhaps overly-participatory art enthusiasts—it almost came to seem surprising that so many images were still there. Were they survivors, or were they rejects—too undesirable to steal? As a friend put it, it was ephemerality over ephemerality.

Truthfully, I’m not sure I would have particularly enjoyed the exhibit in its initial phase; it might have seemed too precious, too overly determined. But the effects of time, and the harshly desolate seaside environment coupled now with the effects of the pandemic were real: these rooms and images had met the elements, and the results were there to see. It occurred to me that I, too, could pull a photograph from the walls, and add to the rate of decay. But I think those photographs need that place—it’s now a whole organism, a living experiment in photographic entropy. I hope some of it is still there, in new form of course, whenever I next visit.

Note: you can see video documentation here of what the installation looked like six months after it opened and information on the 2019 Bombay Beach Biennial here. I would guess about 1/4 - 1/3 of the original photographs currently remain onsite. All installation photographs by the author.